Australia’s future is not its past

If the past is another country, then the future of Australia’s economy after the COVID-19 crisis will be a different universe.

And this crisis provides us with an opportunity to shape it for years, possibly generations, to come. But will we be able to grasp that opportunity?

It’s not as though our recent past has been an unalloyed success. While we can claim almost 30 years of continuous economic growth, this record has been marred of late by a productivity slowdown, wage stagnation and increasing social inequality.

Moreover, we have had to endure a decade-long debate over climate change in which evidence has mattered less than ideology. We have become bystanders to the existential impact of global warming, species destruction and environmental degradation, including the catastrophic bushfires of 2019–20 and coral bleaching on the Great Barrier Reef.

If there is a single factor linking the constituent parts of this experience, it is Australia’s overwhelming reliance on the export of unprocessed raw materials to drive growth and prosperity. However sophisticated the method of resource extraction, the truth is we are sustaining a first-world lifestyle with a third-world industrial structure.

This was the message of the Harvard Atlas of Economic Complexity, which ranked Australia at the bottom of the OECD for "complexity", as measured by the diversity and research intensity of its exports. It is also the logical endpoint of the theory of ‘comparative advantage’, which asserts that we maximise gains from international trade by exploiting our abundant natural endowments in return for imported consumer goods from places that produce them more cheaply.

Even if this theory were true in the past, it no longer holds in a world where manufacturing is undergoing massive transformation in a "fourth industrial revolution", encompassing robotics and automation, artificial intelligence, data analytics and machine learning.

For economies like Germany, Switzerland and Japan, manufacturing and related services underpin high productivity and high-skill jobs. Competitive advantage is achieved not through low-cost mass production but through "smart specialisation" in global markets and value chains.

By contrast, Australia has allowed its manufacturing sector to decline to dangerous levels, now down to around six per cent of GDP from 30 per cent in the 1970s. Even many of the companies that managed to survive the removal of tariff protection in the 1980s and ’90s ultimately succumbed to the high dollar associated with the mining boom.

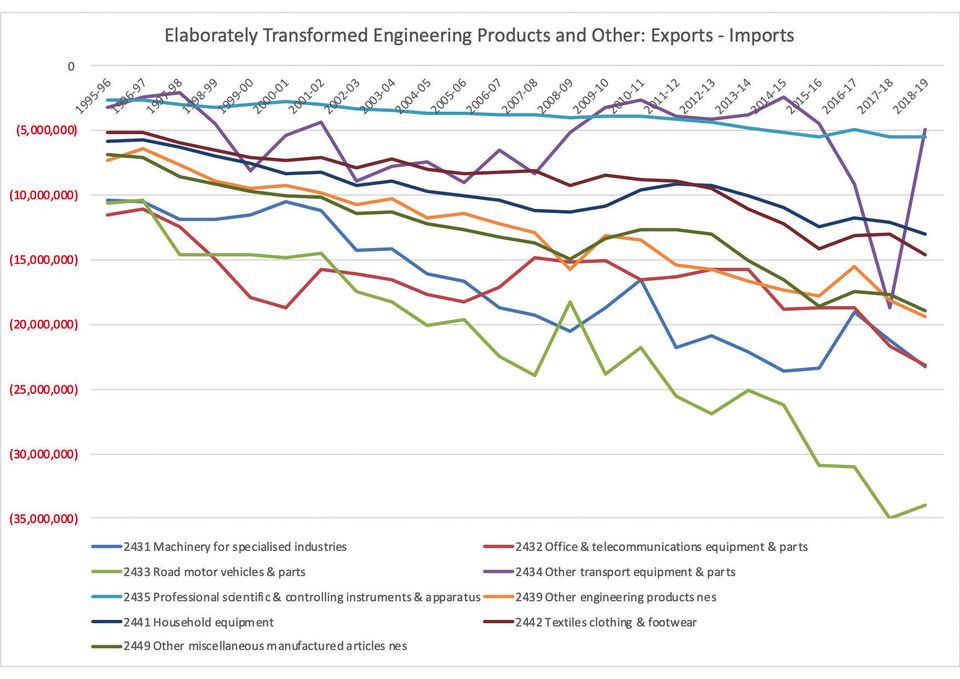

Consequently, Australia’s manufacturing deficit is increasing year on year, particularly in R&D-intensive "elaborated transformed manufactures" (ETMs). While ETM imports have more than doubled to around $215 billion over the last 25 years, ETM exports have increased only marginally to $36 billion, with the widening deficit most acute in engineering products (see graph).

Australia’s widening trade deficit in engineering products, 1995/96–2018/19

Despite much talk of the post-mining boom transition to a more diverse, knowledge-based economy, current examples of Australian manufacturers with a global presence are few and far between. The problem lies not in any lack of talent but in the absence of a coherent and effective national industrial strategy.

While the COVID-19 crisis has exposed and accentuated this problem, it also provides the opportunity for a fundamental redesign of our outdated industrial structure. During the "hibernation" phase of the crisis, the Coalition Government did what it could, with Labor’s support, to retain jobs, strengthen the social safety net and ensure production of urgently required medical equipment.

However, in planning for the longer term, Prime Minister Scott Morrison has also made reference to the bridge that must be constructed to a “better, stronger economy”. Industry Minister Karen Andrews has argued that Australia must “compete on value, not cost”. And Treasurer Josh Frydenberg has raised the prospect of industry support that is “niche, targeted and purposeful”.

In addition, as US economist Richard Baldwin recently noted, “governments will have to undertake detailed thinking on production networks not undertaken since the 1940s . . . The containment policies will need to be intelligently crafted. And the longer the containment policies last, the more important it will be for them to be intelligent, flexible and well-informed”.

This is a major economic challenge. And there is now every chance that, in meeting it, Australia may be able to achieve the political consensus that characterised the Hawke-Keating reforms of the 1980s and ’90s. If we are doubly fortunate, this consensus could even extend to genuine climate action, which has been so obviously lacking up to now.

To this end, the Prime Minister has established a taskforce, chaired by former Dow CEO Andrew Liveris and comprising both industry and union leaders, to identify the steps that should be taken to rebuild and reinvent Australia’s manufacturing capability. The following are some essential measures that might be considered.

First, we must overcome the fragmentation and under-resourcing of institutional policy-making in Australia. A new National Industrial Strategy Commission, or similar body comparable with those in other advanced economies, could develop national priorities in consultation with industry sectors to grow ‘industries of the future’, based on new technologies and business models.

The initial task of this Commission would be to undertake a "knowledge foresight" to identify areas of current and future competitive advantage for Australia, as well as gaps in domestic supply chains. Clearly, enhancing self-sufficiency is not incompatible with a commitment to a more complex globalised economy.

Second, a more systematic approach is required to deepen collaboration between industry and research organisations, possibly around the CSIRO’s designated "national missions". This will require the Government to reverse the decline in public funding of research and innovation, now far below the OECD average and still falling as a share of GDP.

In addition, the national missions will require an implementation strategy at the enterprise level, or they will simply remain abstractions. This might take the form of industry-led innovation hubs – again a successful model elsewhere – which would benefit from shifting resources from the R&D tax incentive to more direct targeted programs.

Third, we should not overlook the contribution of entrepreneurial start-ups to economic renewal, including integration of the digital and physical dimensions of manufacturing, which is a key feature of Industry 4.0. Governments everywhere facilitate start-ups, and scaling up, through support for innovation precincts in cities and regions.

Fourth, the Government can make a big difference for small and medium enterprises with public procurement policy. Too often we see local tenders overlooked in favour of large international companies on a narrow "value-for-money" basis, when these large companies themselves might owe their existence to another country’s procurement policy.

Finally, industrial transformation will depend on the adequacy of our workforce and management skills. This will require measures to compensate for the COVID-19 hit to international student revenues that cross-subsidise university domestic teaching and research, as well as the earlier damage to Australia’s vocational education and training system from market contestability.

The Government’s "whatever-it-takes" intervention to safeguard people’s lives and livelihoods has been clearly justified, but concern has been expressed that this will entail an unprecedented level of public debt. The history of wars and crises tells us that the only way to pay off such debt is to create a new economic growth engine. That new growth engine will be advanced manufacturing.

Roy Green is Emeritus Professor at the University of Technology Sydney, chair of the Advanced Robotics for Manufacturing Hub and chair of the Port of Newcastle.

This article is taken from the recently published digital book

Australia's Nobel Laureates Vol III State of our Innovation Nation: 2021 and Beyond