Defining the mind: Physical, mental worlds collide

Defining the mind: Physical, mental worlds collide

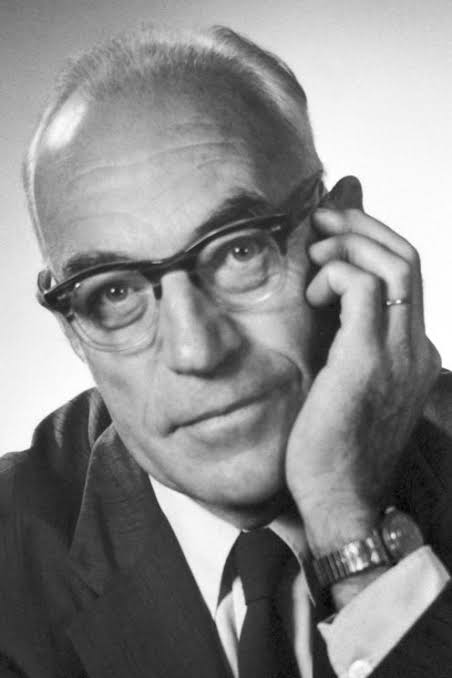

John Carew Eccles 1903 -1997

Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine 1963

Shared with Alan Lloyd Hodgkin and Andrew Fielding Huxley

Shared with Alan Lloyd Hodgkin and Andrew Fielding Huxley

John Carew Eccles had a burning desire to answer life’s biggest questions: How we come to be and how we are what we are, trying to understand the very nature of existence. His work led to an understanding of the central nervous system, including how it works and how it controls the body.

John Carew Eccles had a burning desire to answer life’s biggest questions: How we come to be and how we are what we are, trying to understand the very nature of existence. His work led to an understanding of the central nervous system, including how it works and how it controls the body.

Are you made up of your brain or your mind? Is the essence of who you are controlled by the brain - an organ - or the mind, which has no known physical dimension? Is your mind mysterious, an ethereal controller of your brain, or a complex but wholly explicable product of the brain's chemical, electrical and neurological processes? Indeed, is the mind real or imagined? Start exploring questions like these and you plunge into a maelstrom of conflicting philosophies and sciences; the same ferment of human thought that has pitted atheists and spiritualists against each other throughout the ages. Ponder the existence and function of the mind and you enter into the world of Sir John Carew Eccles, whose obsession with the brain and central nervous system reshaped science's understanding of neurological processes. His research and insights into these complex and controversial mechanisms that define humanity culminated in him being awarded science's highest honour, the Nobel Prize, in 1963. The honour was shared with two British neurology specialists, Sir Alan Lloyd Hodgkin and Sir Andrew Fielding Huxley. Their citation read: "For their discoveries concerning the ionic mechanisms involved in excitation and inhibition in the peripheral and central portions of the nerve cell membrane".

In plain English, the three scientists, individually and together, significantly expanded medical researchers' understanding of the central nervous system, including how it works and controls the body. For Eccles, winning the Nobel Prize was the culmination of his search for the mechanisms by which the mind controls the body. He always said that his quest began as an 18-yearold medical student, when he was struck by an awesome feeling of his own uniqueness; he marvelled at his brain's capacity for thoughts and emotions. Yet perhaps his obsession with the brain started at a much younger age. A memoir entitled Hello Eccles, written by his family, states: "He was born with an uncommonly large head and the doctor told his parents bluntly that this indicated the child would either be an idiot or be brilliant. Anxiously they awaited his development." One of Eccles' daughters, Mary Mennis, said her father once confessed that he had done an IQ test and was off the top of the scale, that his IQ could not actually be tested. Before Eccles' groundbreaking neurological studies that greatly increased knowledge of the mammalian nervous system, the brain was regarded by many neuroscientists as a powerful, albeit poorly understood, biological machine - a haphazard collection of circuits that wire bodily functions via the central nervous system. When processed by the brain, the combined action of all this circuitry, feeding information into and out of the brain, was thought to somehow create the sense of personal control and individual identity. Eccles, also a neuroscientist, considered such conventional views as ridiculously simplistic. In fact, he described many of the more popular theories of the day as "impoverished and empty". While every bit a disciplined scientist with an obsession for rigidly objective experimentation, Eccles nonetheless believed that if the science was going to be credible it couldn't simply dismiss what he called "the mystery of human creativity and uniqueness". He wrote: "Extensive experimental studies have shown that mental acts of attention and intention activate appropriate regions of the cerebral cortex. An intention to move, for example, initiates the firing of a set of neurons of the supplementary motor area about 200 milliseconds before the intended movement takes place. If the mind is the brain, this would mean either that one part of the brain activates another part, which then activates another part, or that a particular region of the brain is activated spontaneously, without any cause, and it is hard to see how either alternative would provide a basis for free will."

FREE WILL OR MIND MACHINE

Eccles believed that the notion of the brain as nothing more than a virtual machine could not stand up to even basic scrutiny as soon as a scientist acknowledged the mysteries that the machine theory could not explain. For example, to sidestep the mystery of that uniquely human capacity to wonder as if it were something that would be learned in the course of time as the brain became better understood was, to Eccles, shoddy science. "I maintain that the human mystery is incredibly demeaned by scientific reductionism, with its claim in promissory materialism to account eventually for all of the spiritual world in terms of patterns of neuronal activity," he wrote.

"This belief must be classed as a superstition and we have to recognise that we are spiritual beings with souls existing in a spiritual world as well as material beings with bodies and brains existing in a material world." Eccles was never shy about including both the philosophical and the anatomical in the course of his research, which went further than anyone had previously gone into whether, or how, both physical and mental states might exist or interact in the nervous system. This was largely due to him being- at that time in his life- a practising Catholic with a strong belief in God, which he took to his research without any sense of contradiction as he peeled away at the mechanics of the human brain and its neurological processes, processes that other scientists believed to be the inner and wholly human origin of spiritual awareness.

In an undated interview with ABC Radio he once explained his scientific obsession this way: "How we come to be and how we are what we are is beyond any understanding. I have been obsessed by this; trying to understand the very nature of my existence. Somehow or other, what is going on in your brain turns into a perception. This is a tremendously important problem beyond any solution, but it is a real problem."

John Eccles, the scientist who defined some of science's most imponderable questions during the 20th century was born on January 27 1903 at Northcote, a suburb north-east of Melbourne's central business district. His father, William James Eccles, and his mother, Mary (nee Carew), were both school teachers, born in Victoria. At the age of 12, Eccles began his secondary schooling at Warrnambool High School. Before entering the University of Melbourne, he spent a year at Melbourne High School studying science and mathematics. He headed the school at the final state-wide exam, shared the state geometry prize and gained a senior scholarship to the University. Although interested in mathematics, Eccles chose to study medicine and started his five-year course in 1920 at the age of 17. He was active in various university societies and sport, gaining a full blue in athletics after setting an Australian universities' record in pole vaulting. Like many students whose courses included the biological sciences, he was strongly influenced by Darwin's Origin of Species. It encouraged Eccles to read widely on both physiology and philosophy and it was when he could not find a satisfactory explanation of the interaction between the mind and the brain that he decided, while still a student, to become a neuroscientist. After reading Sir Charles Sherrington's 1906 book, The Integrative Action of the Nervous System, Eccles applied himself to achieving a Rhodes Scholarship just to be able to work with the pioneering neurophysiologist at Oxford University. "I, at the age of 17 or 18 as a medical student, suddenly came up against a problem. What am I? What is the meaning of my existence as I experience it? And I proceeded to read quite a lot about what the philosophers had said and the psychologists and was profoundly dissatisfied with it. I decided that they didn't know enough about the brain and the brain was the essence of all my consciousness and everything that I knew myself to be. I decided that I would learn something myself about it." Eccles completed his medical course in February 1925, gaining first class honours, first place and several clinical prizes. He graduated with the degrees of Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery, and had already been awarded the Rhodes Scholarship for Victoria. After six months as a resident medical officer at St Vincent's Hospital in Melbourne, he left Australia in August 1925 and arrived in Oxford in October. Eccles then worked closely with Sherrington until 1931 in the Oxford Neurophysiology School, which produced major advances in neural understanding. Sherrington, also a published poet, was 74 and his experiments with Eccles were the last in which he actively participated. However, the pair formed a deep friendship that would last until Sherrington's death. Later in 1952, when Eccles was in England to deliver the eight Waynflete Lectures (dealing with neurophysiology and mind-brain problems) at Magdalen College, Oxford University, he visited Sherrington at his Eastbourne nursing home on England's south coast just days before his great mentor died. In 1932, Eccles became a Staines Medical Research Fellow and two years later, lecturer in physiology at the same college in Oxford. In the 1920s, the Oxford Neurophysiology School, under Sherrington, led the world in the field of mammalian central nervous system physiology. It was also a time of controversy between the exponents of rival chemical and electrical theories on the nature of the process of transmission at the terminal junctions (synapses) of nerve cells (neurons). Although there was strong evidence of chemical transmission at excitatory and inhibitory synapses in the peripheral nervous system, synaptic transmission in the central nervous system was widely considered to be an electrical process.

CHEMICAL RESISTANCE

Eccles resisted many aspects of the chemical transmitter theory. The techniques then available for studying central synapses were simply inadequate for determining the nature of the transmission process, but the debate was important in defining problems and stimulating considerable experimental work. The eventual victory of the chemical theory was another 20 years away. For a while Eccles looked like he would stay at Oxford for the duration of his academic career, but in 1937 he was drawn back to Australia by a position at the Kanematsu Memorial Institute of Pathology at Sydney Hospital. His mentor, Sherrington, had retired from his post in 1936 and Eccles was disappointed at the direction that research was taking at Oxford. He was also increasingly worried about the political uncertainty in Europe. "There was the ominous rise of Hitler against the unprepared Western Alliance, so I decided, perhaps unwisely, to return to what seemed the security of Australia. There was the opportunity to create in Sydney a research institute matching the Hall Institute at Melbourne Hospital with Kellaway and Burnet. I accepted the directorship of the Kanematsu Institute at Sydney Hospital." (Dr Charles Kellaway, later Sir Charles, was director of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, transforming it into a research facility specialising in physiology, biochemistry and bacteriology. Eccles said that in retrospect, he felt he should have stayed in England and weathered the storm but instead, "I embarked on my odyssean journeying, never to return to my beloved England. It was a fateful choice." He found the academic isolation severe. "The Sydney University Medical School was a very dim place, being little more than a teaching institution. Unbelievably, it was completely locked up by guards at 5pm. Even the professors had to scurry out to avoid imprisonment for the night! " At the Kanematsu Institute he led a team studying the actions of chemical substances on the transmission of nerve impulses to muscles. One of the team members was Bernard Katz, a refugee from Nazi Germany, and a key member of the research team that eventually proved the chemical theory in nerve transmission. It was Katz who was able to show how chemical transmitters released from nerve endings produce electrical currents, and that the chemical alters the configuration of molecules in the cell membrane. This allows ions to flow into muscle fibres and generate electrical currents. Katz was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1970. Katz's collaboration with Eccles was interrupted by Japan entering the war- Katz joined the Royal Australian Air Force in 1942 and Eccles found himself working on the problems of communication in the noisy environment of aircraft and tanks. The last straw, however, came when the hospital board decided to add two floors to the Kanematsu Institute to accommodate resident medical staff, effectively curtailing future expansion of the research laboratories.

Eccles resigned in late 1943 and moved to Dunedin, New Zealand as professor of physiology at the Otago Medical School. His new job required him to take on a heavy teaching load, so Eccles, who would be called "Prof" and eventually "Jack" by younger colleagues, conducted many of his experiments late at night and in the early morning. Many people, when describing Eccles, mentioned his enormous energy, along with a powerful personality. It was in New Zealand that Eccles met science philosopher Karl Popper, who became a pivotal influence on Eccles and his research. "The year 1944 was important in my scientific life above all my post-Sherrington years, because my intimate association with Karl Popper dates from that time," Eccles said. "Many people, including myself, had our scientific lives changed by the inspiring new vision of science that Popper gave us." Popper was a vigorous proponent of the "falsifiability" of hypotheses as the only true test of validity for a scientific theory. In other words, he argues that proving a proposition to be valid was not good enough - just as much effort had to go into deliberately trying to disprove it as well. Eccles found this a liberating way to approach experiments. It meant he could be absolutely daring in developing any hypothesis, and rejoice even when he proved it wrong because this in itself was a scientific success. Eccles would later say this greatly lifted his conceptual power because in many ways the shackles were off. It removed any hesitation about proposing a theory that might later be proved flawed. Eccles and Popper eventually collaborated on the influential 1977 book The Self and Its Brain, a fascinating probe into the body-mind, self and soul puzzle. It remains the most cited of all of Eccles' philosophical writings.

Concerned that his heavy teaching load in Dunedin was limiting his competitive edge, Eccles returned to Australia in 1952 to take up the foundation chair of physiology in the John Curtin School of Medical Research at the recently established Australian National University in Canberra.

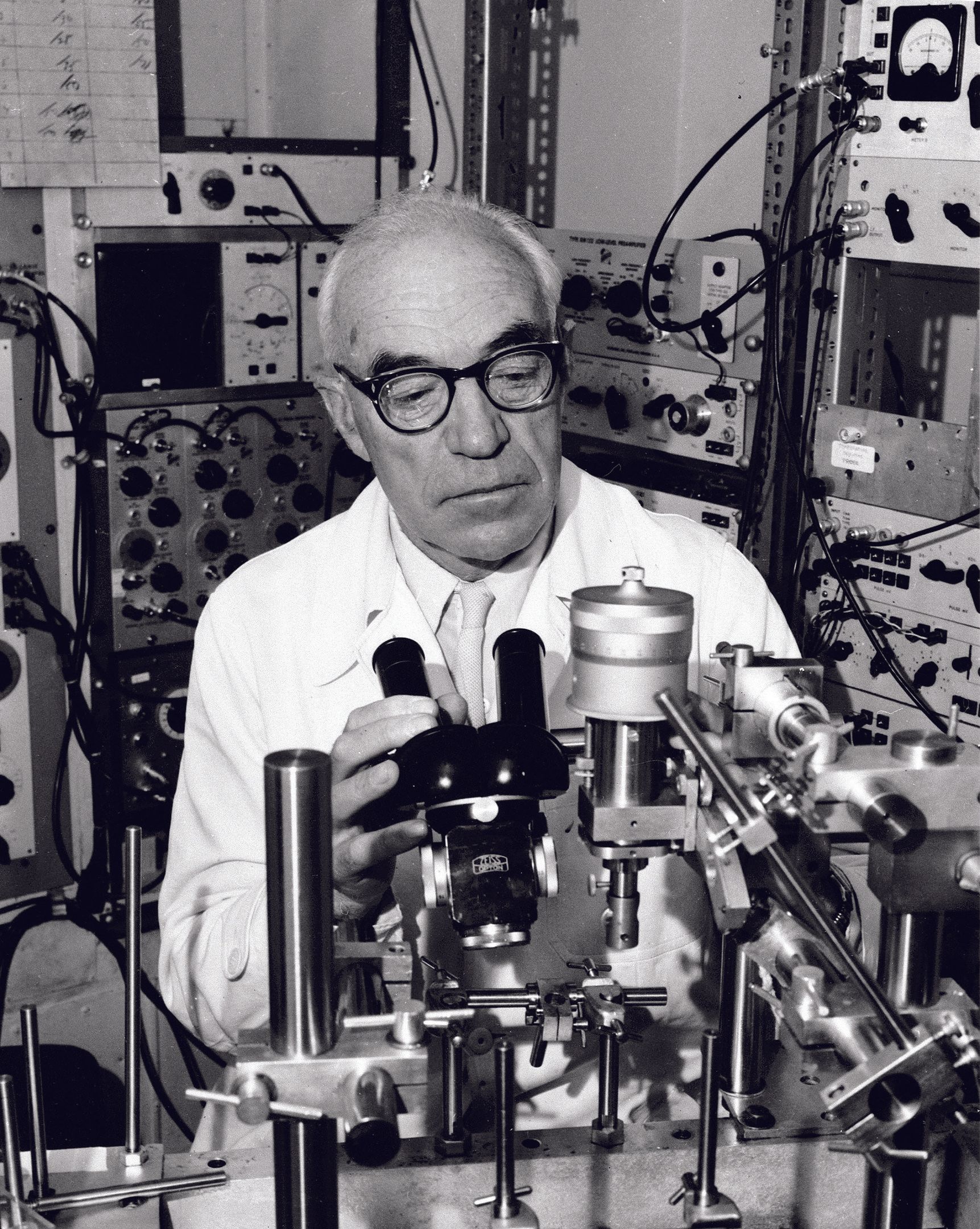

He regarded his "14 golden years" there as the most productive and enjoyable period of his career. Colleagues remember him as honest and occasionally terse. However, Eccles would unreservedly heap praise upon anyone who had made significant discoveries or progress. In Canberra, Eccles made significant contributions to the understanding of the ionic basis of central nervous system excitation and inhibition, and the nature of chemical transmitters involved in this. It was for this work that he received the Nobel Prize in 1963. His daughter, Rose Mason, was working with him as a researcher in Canberra when he received the Nobel Prize news. She recalled the momentous occasion, which Eccles downplayed in his own writings: "We had a wonderful celebration in the lab and we presented him with a candlestick," she said.

FORCED RETIREMENT

In 1966, despite a brilliant career and international acclaim, Eccles crashed head-on into the cultural apathy that dogged academic achievement in Australia. Despite his knowledge, experience and zest for science and life, he found absolute disinterest within the nation's bureaucracy and university hierarchies in finding a way around retirement at the compulsory age. Reluctantly, he left Australia again and was welcomed with open arms by the American Medical Association's Institute for Biomedical Research in Chicago. It was not a happy or successful period for Eccles, and he moved three years later, this time to be distinguished professor of Physiology and Biophysics at the State University of New York. His departure from his home country had also been coloured, in the eyes of some, by his divorce from his wife Irene, with whom he had nine children, and his marriage shortly afterwards to Dr Helena Taborikova, a Czechoslovakian neurophysiologist whom he had met at a scientific congress in Prague in 1963. Eccles' daughter felt her father's decision to leave Australia again had more to do with personal than professional circumstances. When interviewed for a Radio National program celebrating her father's centenary, she said her parents had "drifted miles apart". "My mother had become very religious and she went to religious meetings. She got up and went to daily mass and this used to irritate him because he'd get to bed at two or three and the alarm would go at six and, you know, wake him up. Both were incompatible in many ways, their characters, and he was much more open - he loved meeting people." Despite the incompatibilities, daughter Mary Mennis said her mother was shocked to hear - via a friend who heard it on the evening news - that Eccles, who was in Chicago, was filing for divorce. Eccles ceased to be a practising Catholic. When his second wife, Taborikova, was interviewed on Radio National, she said he could no longer accept many of the dogmas of the church. When Eccles did finally retire in 1975 at the age of 72, he moved to the "idyllic mountain surroundings" of Contra in Switzerland. Both he and Helena, who outlived him, were sad that Australia had not accommodated his willingness to keep experimenting and writing well beyond retirement age. He travelled widely throughout Europe and the United States and played a prominent role in the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War organisation, which was involved in the formation of ICAN, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons. ICAN, which has its roots in Melbourne, is Australia’s first recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. Eccles also continued to wrestle intellectually with a new generation of researchers. In Frankfurt, in 1993, during a celebration of his 90th birthday, he was still pushing advanced ideas on cerebral function and the nature of consciousness and the self-psyche mind-body conundrum.

MENTAL INTERACTIONS

Eccles came to believe that humans have a non-material mind or self that acts upon, and is influenced by, our material brains - a mental world in addition to the physical world, and that the two interact. As for what the mind actually is, Eccles conceded that it could not be pure nothingness, otherwise it could not exist, in which case he reasoned it to be composed of finer grades of energy-substance. Indeed, he suggested our inner constitution might comprise several non-physical levels. Eccles always had plenty of opponents, however. In his last book in 1994, How the Self Controls Its Brain, he was buoyed by advances in quantum physics and the latest discoveries about the microstructure of the neocortex, which he felt were on the way to supporting his proposition. Eccles called the fundamental neural units of the cerebral cortex dendrons, and he proposed that each of the 40 million dendrons is linked with a mental unit, or psychon, representing a unitary conscious experience. In willed actions and thought, he proposed that psychons act on dendrons and momentarily increase the probability of the firing of selected neurons. Eccles remained in basic agreement with the neo-Darwinian theory that evolution is driven by random genetic mutations followed by the weeding out of unfavourable variations by natural selection. However, he added to this his belief in a divine providence operating over and above the biological evolution. As for what happens after death, Eccles had little option but to fall back onto his personal perspective: "We did come to be by something we do not understand at all, and therefore in our apparent ceasing to be, with death, it is the same problem. So I should say we have hope because we know nothing, and we should not dogmatise it. This is part of the message I have for humanity, that there is such tremendous mystery, so little is known, and the wonder is so enormous that we must have hope." Eccles took the scientific exploration of the mind and brain as far as anyone had been able to push, but even he was forced to concede that perhaps the meaning of life might always be a mystery. He said: "For me the one great question that has dominated my life is: what am I?" After suffering ill health from 1994, John Eccles died on May 2, 1997 at Locarno, Switzerland. At Eccles request, he was buried in Contra near his last home.

Vital Statistics:

Name: John Carew Eccles

Born: January 27 1903, in Northcote, Melbourne

Died: May 2 1997, in Locarno, Switzerland

School: Warrnambool High School, Melbourne High SChool

University: University of Melbourne, Oxford University

Married: Irene Frances Miller, of Motueka, New Zealand in 1928, divorced 1968; married Helena Taborikova, of Prague, Czechoslovakia, 1968

Children: Five daughters, including Rosamond (Rose) who worked at the Australian National University with him as a researcher from 1955-66, and four songs with Irene Miller

Lived: Australia, New Zealand, the United States, England and Switzerland

Awards and Accolades:

1927-29: Christopher Welch Scholar, Oxford

1932-34: Staines Medical Fellow

1952-66: Professor of Physiology, Australian National University

1952: Waynflete Lectures, Magdalen College, Oxford

1958: Knight commander

1962: Royal Medal, Royal Society

1963: Nobel Prize in Physiology of Medicine

1966: Foreign Associate, National Academy of Sciences

1968-75: Distinguished Professor of Physiology and Biophysics, State University of New York at Buffalo

1990: Companion in the Order of Australia

1993: 90th birthday marked by the establishment of the Sir John Eccles Lecture, University of New South Wales

Why he was awarded the Nobel Prize:

Sir John Eccles’ Work with the brain and central nervous system reshaped science’s understanding of neurological processes. His discoveries expanded the knowledge available surround the central nervous system including how it works and how it controls the body. He shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with physiologists and biophysicists Sir Alan Lloyd Hodgkin and Sir Andrew Fielding Huxley.

In particular, his work concerned the electrical changes, which the nerve impulses elicit when they reach another nerve cell. He made significant contributions to the understanding of the central nervous system including excitation and inhibition, and the nature of chemical transmitters involved in this. Eccles showed how excitation and inhibition are expressed by changes of membrane potential.

When the response is sufficiently strong to cause excitation, the membrane potential decreases until a value is reached at which the cell fires off an impulse. This impulse travels through the nerve fibre of the cell and causes contraction in a muscle. He showed how excitation and inhibition correspond to ionic currents, which push the membrane potential in opposite directions.

By understanding the nature of the events in the peripheral and central nervous system, a greater understanding of nervous action has been achieved. Eccles believes that the origin of each of us stems from codes of genetic inheritance and the most significant questions we can ask scientifically concern the working of our nervous systems – the reception, communication and storage devices that subserve all our perception, thoughts, memories, actions, creative imaginations, and ideals.