KEEPING YOUR NERVEBy Julian Cribb

KEEPING YOUR NERVE

By Julian Cribb

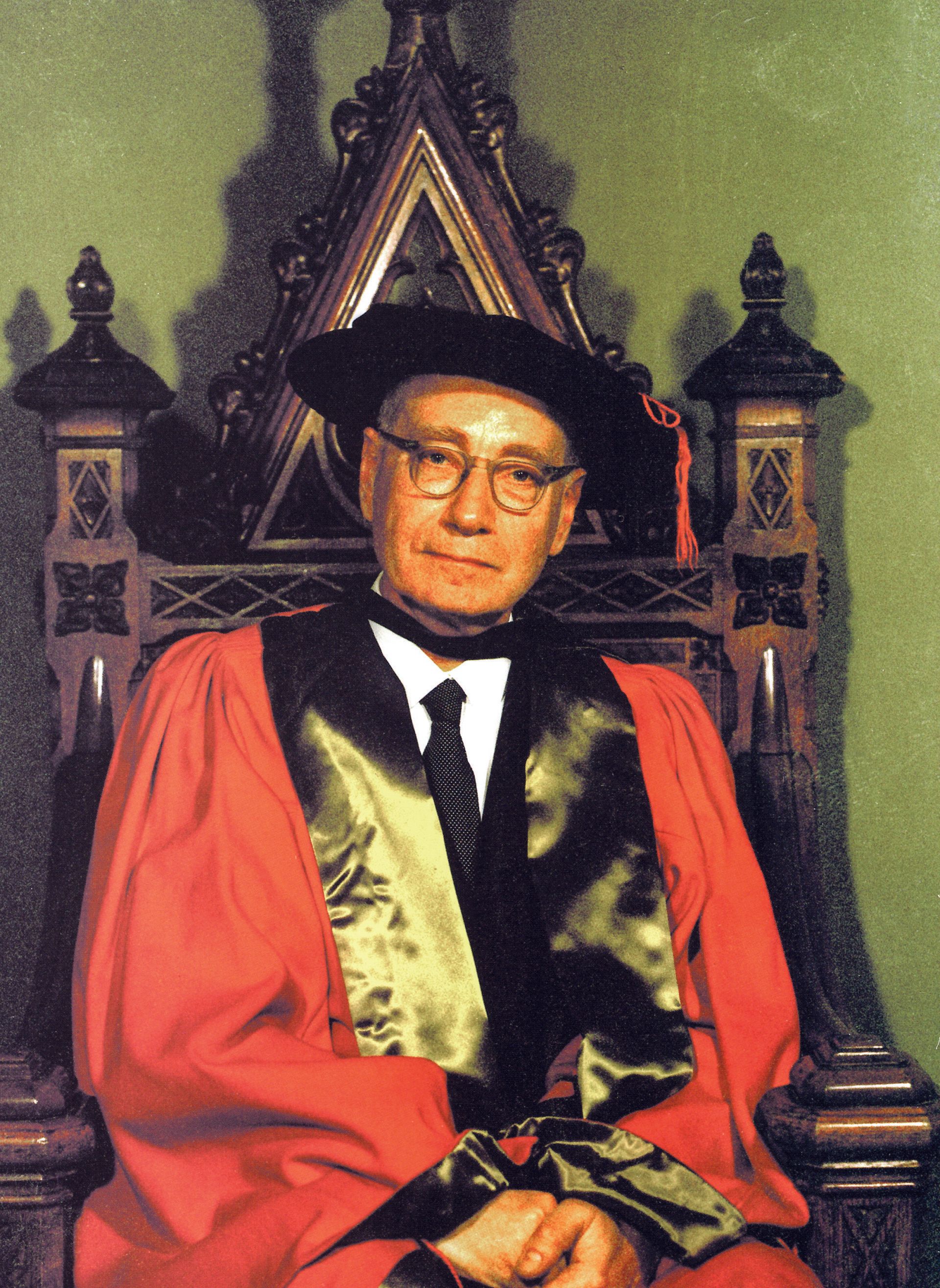

Bernard Katz 1911-2003

Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1970

Shared with Ulf von Euler and Julius Axelrod

From fleeing persecution in Germany to contributing to the world’s understanding of the human nervous system, Bernard Katz’s life was anything but ordinary.

From fleeing persecution in Germany to contributing to the world’s understanding of the human nervous system, Bernard Katz’s life was anything but ordinary.

Bedraggled, penniless and feeling distinctly like Dickens’ David Copperfield arriving on the doorstep of unknown relations, the young refugee nervously ascended the long, creaking flight of stairs to the top floor of the University College, London.

It was a defining moment for the 23-year-old Bernard Katz. Behind him lay the chasm of Nazi Gemany that in February 1935 was already beginning to engulf Jews and scientists like him. All his hopes were pinned on an outspoken British physiologist and Nobel Laureate, Archibald Vivian Hill (AV) whom, a year earlier, had launched a scathing attack on the treatment of scientists under the Nazis, provoking the wrath of the Third Reich’s scientific gauleiter (district political leader), the Nobel Laureate Johannes Stark.

Katz was reasonably confident of a sympathetic hearing with Hill. However, he had no inkling that the daunting staircase was also taking him towards a series of brilliant advances in human knowledge, an Australian citizenship and a lifetime love-match with an Australian girl. It was also to lead to a British knighthood and to science’s highest honour, the Nobel Prize.

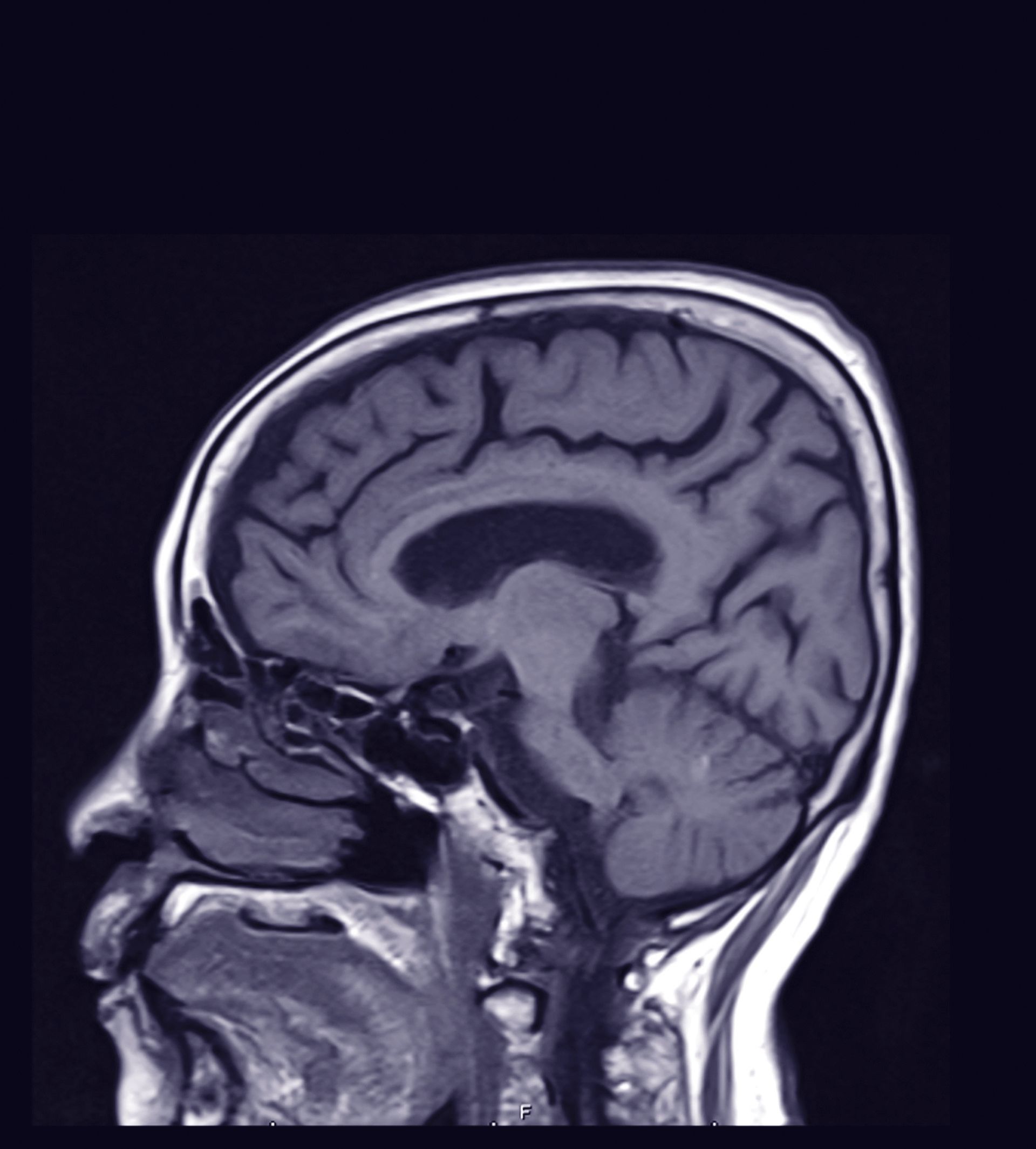

Bernard Katz worked out how nerves communicate with the muscles and helped to lay the foundations for modern neuroscience and neuromedicine.

He was born in Leipzig in 1911, the only child of a Russian father, Max Katz, and a Polish mother, Eugenie Rabinowitz. However, although he was born in Germany, Katz never acquired German nationality. For his first six years he was a subject of the Tsar of Russia, as his fur merchant father had migrated to Leipzig in 1904 to escape the internal unrest that preceded the Russian Revolution. As a result, the family was regarded as enemy aliens during World War I. Then the Revolution came and any expatriate Russians who did not wish to become Soviet citizens ended up with no citizenship at all.

Katz later said in The history of neuroscience in autobiography, Volume I Larry R. Squire, Society for Neuroscience: a Society for Neuroscience publication: “I did not foresee I was going to remain stateless and without a passport for the first 30 years of my life until I finally acquired this much coveted possession in Sydney, Australia.”

At age nine, Katz had an early taste of what it meant to be an alien Jew when he was refused entry to the leading secondary school in Leipzig, even though he easily topped its entrance examination.

He was instead schooled at the König Albert Gymnasium, which had a strong reputation for the humanities and classics. Yet even in the school corridors, Katz was hardly protected from the antisemitism being encouraged by the fledgling Nazi party. In 1922, at the tender age of 11, Katz heard about a fellow student who had “called the boys together and informed them of a marvellous plan that his father had discussed with him at home.”

The plan was that the Jewish population of Leipzig should be invited to assemble in the underground fair hall and, after closing the doors, should be killed off by filling the hall with poison gas."

“I did not foresee I was going to remain stateless and without a passport for the first 30 years of my life until I finally acquired this much coveted possession in Sydney, Australia.” – Bernard Katz

Despite all of this, Katz prospered at school. He interspersed his studies with chess - for which he developed a lifelong passion reading, walking and swimming. The normal German high school curriculum took nine years. Katz forged ahead so strongly in his studies that he was encouraged to skip a year, and thus spent only eight years (1921-29) at the Gymnasium. His school reports were excellent, save for subjects such as gymnastics and singing, in which he freely admits his performance was deplorable. He often tried to avoid those classes.

Katz was a quiet, bookish and solitary child. He said: "I was never what one would call a loner but I kept away from gatherings. I did have good friends, but usually only one at a time." Among these was a young Jewish scholar Heinz Wydra, with whom Katz shared a desk and who introduced him to a way of thinking that later held significance for his approach to science. It was Wydra who taught Katz the game of chess. In Katz's later years, his addiction to chess was replaced by a similar obsession with physiological experiments. "The excitement produced by the occasional successful experiment was similar to the enjoyment of a good performance at chess," he said. "In both cases, the sudden flash of insight after a long struggle in the dark and the intuitive vision of a solution to a seemingly intractable problem are exhilarating experiences which one encounters in both kinds of activity."

During his last three school years, Katz had to choose between continuing his Latin and Greek and a more mathematical and scientific curriculum. Against his character, he opted for the classics because they left him more time to pursue his love of chess. He then "tended to drift off to one of the cafes in Leipzig which had been invaded by chess players", spending long hours over the chequered board nursing a single cup of coffee. Katz later regretted this youthful indulgence, not so much because he missed out on the natural sciences, which he quickly caught up with when he undertook pre-university courses, but because he did not pursue his maths.

Katz embarked on his medical studies at the University of Leipzig in April 1929. A lecture by physician and physiologist Viktor Freiherr von Weizsäcker on the social impact of medicine left a huge impression on Katz, as he realised that there could be great intellectual satisfaction in being a doctor.

CONFRONTING PREJUDICE

Throughout school, Katz had encountered occasional- and to him inexplicable- examples of prejudice on account of his racial background as a Russian Jew. As an Ost Juden, or Jew from Eastern Europe, he was surprised to find that even Jews of Germany and Western Europe, as well as non-Jews, looked down on him.

Weizmann promised to try to get some funds to help the young scientist. It turned out to be no more than £50 a year for two years, but the elated Katz hastened home to complete his degree and plan his escape.

The World War I Marshal von Hindenburg, Weimar Germany's second president and the appointee of Adolf Hitler as Chancellor in 1933, was already clearly favouring the Nazi Party and Hitler. "I finally decided there was little future for the decent people and none at all for me in Germany of those days," Katz said. "It was at that time, in the summer of 1932, that I began to make plans to emigrate as soon as I had completed my medical course." Meanwhile, the challenges of university study were fuelling in Katz the prodigious focus and appetite for understanding that characterised his life's work. Katz had the benefit of an outstanding physics teacher in Dr Peter Debye, who a few years later gained the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. The young student also spent time in the Institute for Medical History in Leipzig, gaining a broader understanding of the social context of his studies. Here he shared an enthusiasm for ideas with like-minded students and eminent philosophers, historians, and writers on medicine. Katz was by now an active Zionist, running public appeals to raise funds to buy land for the new settlers in Palestine. He was also working part-time for two ear-nose-and-throat specialists, learning the basics of the medical trade and supporting himself financially. As his studies progressed, he homed in on what was to become his life's work -the study of how nerves function. "I was attracted to the subject of neurophysiology at quite an early stage, from about 1930 onwards. In those days, the establishment of the laws of electric excitation of nerves and their precise mathematical formulation were regarded as a great thing. In retrospect it seems a somewhat naive approach." He said that the exact fitting of so-called "strengthduration" curves to electric stimuli of various shapes and intensities was considered a wonderful achievement, even though it was only a formal exercise which shed little light on the physical mechanism of excitation. "Nevertheless, I felt it was fascinating that one could made accurate and repeatable measurements of electric excitability on living tissues and express the results by a simple mathematical equation." According to Katz, all one needed to do the experiments were some calibrated boxes of simple electrical gear, resistances, condensers and an isolated nerve-muscle preparation of a frog.

ESCAPE

As he approached his final exams, Katz found the political atmosphere around him thickening. "I felt increasingly revolted by the behaviour of the majority of my fellow students who no longer bothered to conceal their Nazi sympathies and anti-Semitic vulgarities," he said. "I made use of every opportunity I could find to withdraw into the solitary atmosphere of my laboratory." Many of Katz's most respected tutors were also starting to display support for Hitler. His isolation was further evidenced when, in order to win an academic prize, he had to submit an essay under a pseudonym. Katz chose that of Johannes Muller, the father of German physiology. He won the prize but was not officially allowed to receive it- although his professor later slipped him the money under the counter. While still a student, he also had two research papers published. One of them caught the eye of one of AV Hill's colleagues, physiologist Ulf von Euler (with whom Katz was later to share the Nobel Prize). "When the Nazis took over early in 1933, I still had some 20 months to go before completing my medical course," Katz recalls. "It was not at all clear whether I would be able to do so. For me, the only practical alternative was to join the exodus to Palestine and try to make myself useful in a kibbutz." At the urging of his tutor, however, Katz decided to stick it out. In 1934, he read in the English journal Nature of AV Hill's stinging critique of the policies of Nazi Germany towards scientists. Katz decided that, if it was possible, he would emigrate and go to work with Hill. His friends put him in touch with the famous Zionist leader Dr Chaim Weizmann. Meanwhile, British relatives promised to try to get him a visa no easy task for a stateless person. To meet Weizmann, Katz had to slip across the border into Czechoslovakia to Karlsbad. Weizmann promised to try to get some funds to help the young scientist. It turned out to be no more than £50 a year for two years, but the elated Katz hastened home to complete his degree and plan his escape. "At the beginning of February 1935, I packed my bags and, equipped with travel tickets, a Nansen certificate (for stateless persons) with a temporary British visa, and the princely sum of £4, I took the train to Holland," Katz said. "l transferred to the Channel ferry at Flushing and arrived at Harwich the next day." The following day he reported to Hill in London to begin what he later called "the most inspiring period of my life". Under Hill, whom Katz would later acknowledge as "the person from whom I have learned more than anyone else, about science and about human conduct", he studied the fundamental properties of synapses, the junctions across which nerve cells signal to each other and to other types of cells. Researchers had known since Italian physiologist Galvani {1737-98) that nerves were sensitive to electric discharges and then found that nerves actually generated minute amounts of electricity themselves. But much remained to be discovered. Katz was accepted as a PhD student by Hill at Uni versity College, London (UCL), working in his laboratory until August 1939. He liked to joke that Hill only took him on "as an experiment". Although Katz had arrived at UCL speaking linle English, his writing style was simple, precise and unpretentious, something that he anributed to excellent teachers at the König Albert Gymnasium. Although the scientific papers that Katz wrote decades ago would have to be added to today, not one of his beautifully constructed sentences would need to be corrected. He completed his doctoral studies in 1938, and was awarded the degree of Doctor of Science (London University). He also won a Beit Fellowship, then regarded as the premier award in the biophysical sciences. In 1939, as a Carnegie Research Fellow, Katz was invited to study with John Carew Eccles, who was to win the obel Prize in 1963 at his laboratory at Sydney Hospital (see Finding the essence of what we are). Katz arrived in Australia a month before World War II broke out.

In Sydney, Katz teamed up with Hungarian-American neurophysiologist, Stephen Kuffler, who had recently arrived from Vienna. For the next two years, Eccles, Katz, and Kuffler worked together on transmission at the neuromuscular junction - the point where the nerves communicate with the muscles - producing landmark papers and forming lifetime friendships. This work laid the ground for the modern understanding of how one cell communicates with another. At the time, a fierce dispute was raging among researchers about how the nerves communicated with the muscles - whether the electrical nerve impulse leapt across the nerve-muscle junction or whether synaptic transmission was mediated by the release of a chemical messenger (acetylcholine) as had been proposed by English pharmacologist Henry Dale in the 1930s. Although Dale's ideas were gaining acceptance, Eccles continued to argue strenuously in favour of purely electrical transmission. Katz admitted that he and Kuffler would have "the occasional stand-up fight" with Eccles over the question. Katz later liked to recall an incident in which he was helping Eccles mow his lawn, only to shear through the power lead to the electric mower, narrowly escaping a lethal shock. To avoid further accidents, Eccles hastily swapped the electric mower for a petrol-driven one. Katz would say that this was the precise moment he converted Eccles from "electrical" to "chemical" transmission between nerves and muscles. Katz was naturalised as an Australian citizen in 1941. With war clouds spreading, he felt a strong obligation to serve his adopted country and he joined the Royal Australian Air Force in 1942. He spent the remainder of the war in New Guinea and the Pacific as a radar officer. In Australia Katz met a young, non-Jewish Sydney woman, Marguerite (Rita) Penly, who would become his life companion.

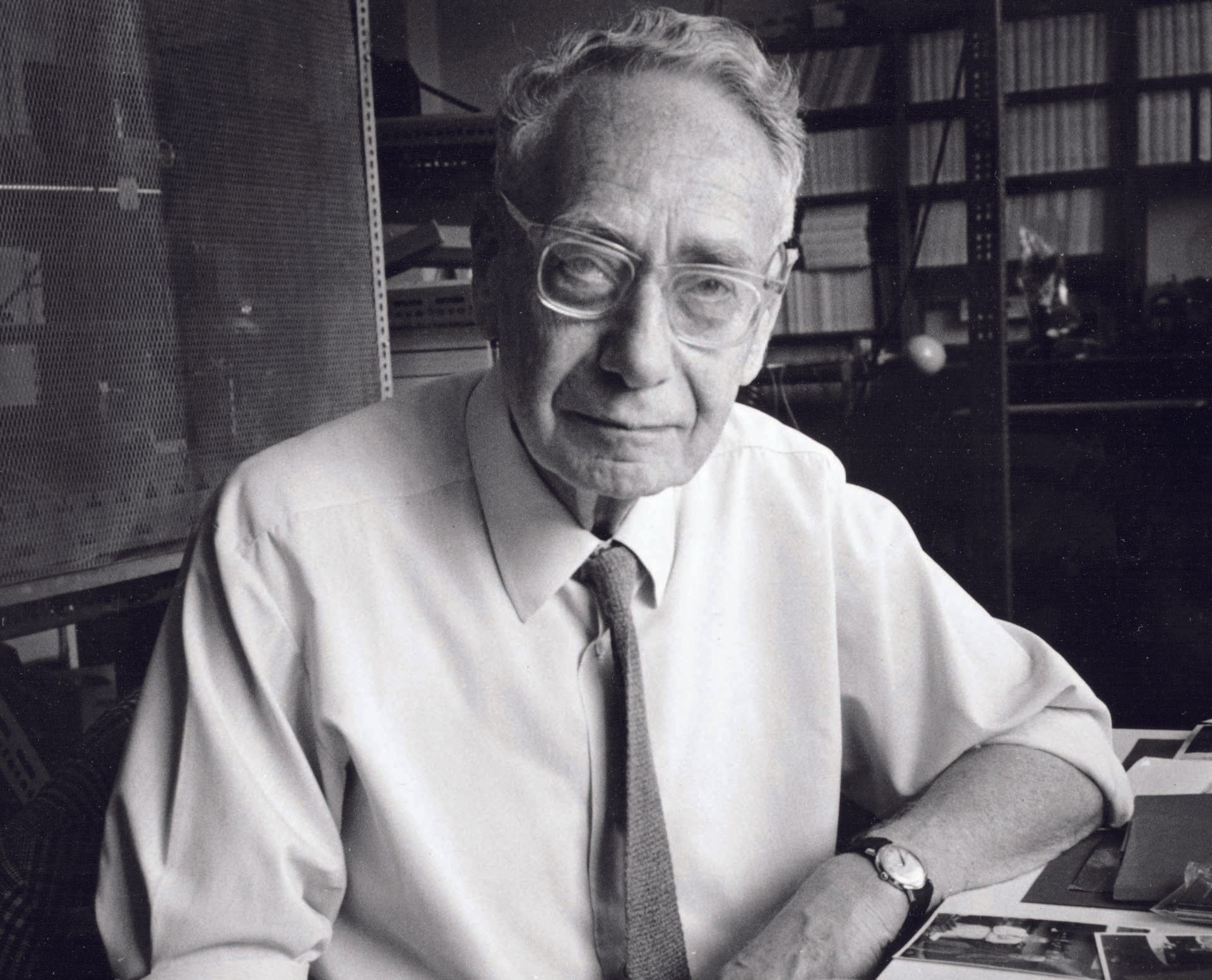

His department became a Mecca for postdoctoral students from all over the world. His influence on the training of a large number of the world's greatest scientists was huge.

They married shortly after World War II ended in 1945, and had two sons, David and Jonathan. For Katz, his jaunts with Rita to meet up with friends in Europe, Israel and America, were among his happiest times. The newly married couple returned to England in 1946; there, Katz rejoined AV Hill's team at UCL and helped set up the Biophysics Department. There he embarked on some of his most important work. The new electrophysiological laboratory was soon in operation, using war-surplus electronic apparatus that the team had scrounged, rebuilt and recalibrated. In 1952, when Hill decided to retire, Katz succeeded him as professor and head of department, leading it to become what colleagues later regarded as "one of the shining pinnacles of British biomedical science, attracting talented postdoctoral workers from around the world". In the same period, he also began a key collaboration with the Marine Biological Labs at Plymouth on England's south coast, studying the nerve currents in squid. Much of Katz's work in these days focused on the biochemistry and action of acetylcholine, the transmitter molecule (or neurotransmitter) with which nerves activate muscles.

GROUNDBREAKING DISCOVERY

In 1950, Katz and his colleague Paul Fatt, made an accidental but groundbreaking discovery. Even when it was supposed to be at rest, the end region of the muscle was fizzing with spontaneous electrical activity caused by the discharge of packets of molecules of acetylcholine from the nearby nerve ending. They revealed that the acetylcholine opens minute aqueous (watery) pores in the muscle cells which allow the electrical current to flow through, causing the muscle to contract. Their experiments demonstrated these pores were the basis of chemical synaptic transmission- the means by which the nerves signal. The pores later came to be known as ion channels and are the basis for-all nerve activity as well as many other cell functions. The team then turned its attention to the second step in the transmission process, the mechanism by which acetylcholine activates its receptors.

In 1957, del Castillo and Katz proposed a two-step model by which the receptor of the nerve signal was activated. This model still forms a starting point for discussion of receptor mechanisms. During the 1960s, Katz and Mexican neuroscientist Ricardo Miledi returned to the issue of transmitter release, undertaking a series of studies. Their work not only provided some of the first definitive evidence for the idea that calcium entry was essential to transmitter release but also allowed the input-output of a single synapse to be studied. Further groundbreaking work followed in the early 1970s and their studies were so original that their first two Nature papers cited only four references to other scientific papers. In 1967, Katz gained the Royal Society's prestigious Copley Medal and, in 1970, recognition of his achievements was crowned with the award of the Nobel Prize, which he shared with Ulf von Euler of Sweden and biochemist and pharmacologist Julius Axelrod of the United States. The Prize was for "their discoveries concerning the humoral transmitters in the nerve terminals and the mechanism for their storage, release, and inactivation". Katz's work had immediate influence on the study of organophosphates and organochlorines, the basis of new post-war study for nerve agents and pesticides, as he determined that the complex enzyme cycle was easily disrupted. While Katz's research into nerve processes was of the most fundamental kind, it also came to have immediate significance amid the rising public concern about the effect of toxic chemicals. It was clear that the delicate electrochemical processes involved in nerve signalling could be easily disrupted. This provided other researchers with a powerful means for exploring the effects of the chemical on the human nervous system - including why they caused lethal paralysis - as well as opening new possibilities for the treatment of brain and nerve disorders. Although Katz trained only five PhD students (including Liam Burke, an emeritus professor of physiology at Sydney University), his influence on his science was prodigious. A colleague recalls: "His department became a Mecca for postdoctoral students from all over the world. His influence on the training of a large number of the world's greatest scientists was huge." And while BK, as he was known to colleagues, could seem forbidding (there are some who recall traumatic experiences in presenting the first draft of a paper to him), there are stories of his jokes and light-hearted asides that cut through the pomposity of boring committee meetings. In the latter part of his research career, Katz became interested in the biochemistry of the pineal gland, in particular, its production of melatonin in response to light. Although generally viewed as an Australian or British scientist, Katz's German origins and Zionist beliefs were recalled and celebrated in 1993 with the creation of the Bernard Katz Minerva Center for Cell Biophysics. This was a German-Israeli joint venture embracing the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa and the Max Planck Institute for Medical Research in Heidelberg. After retiring as head of biophysics at UCL in 1978, Katz, who had never entirely lost his German accent, remained active in research administration, working with the research council of the Royal Society as one of its two secretaries. UCL colleague, pharmacologist David Colquhoun, remembers that even' in retirement, Katz "continued to referee papers with an astonishing speed, often within a day or two, and he took a direct and lively interest in new developments for many more years. In the 1980s I remember him coming, almost running, down the stairs, asking to see David Ogden-at that time a post-doc in my lab- because he'd seen an abstract that David had submitted for a Physiological Society meeting and wanted to discuss it." Katz was devastated in retirement when his wife Rita developed a prolonged illness. Even though he was in his late 80s and frail, Katz made the long journey to visit her twice a day. Katz, who shared his wife's love of literature, was widowed in 1999. In April 2003, the stateless alien who had the nerve to change the world died at the age of 92. Of his life, The Times newspaper reported: "The work of Sir Bernard Katz constitutes an extraordinary contribution to our understanding of the nervous system. In his research he combined an uncanny instinct for separating the important from the trivial. "Characteristically, he would approach a fundamental problem ... and by tackling the question in a new manner, opened up fields that had never been dreamt of."

REFERENCES

Bennett, Max, obituary April 2003

Cull-Candy, Stuart & Jenkinson, Donald, 2003

Carmody, John, obituary May 7, 2003

Encyclopaedia Britannica

International Brain Research Organisation

Katz, Bernard, An Autobiographical Sketch, Deutsches Museum Bonn

Les Prix Nobel, 1970

The Scientist, Mayor, Susan, obituary, April 30, 2003

Nature Neuroscience 6, obituary The Guardian, obituary April 24, 2003

The Independent, Colquoun, David, obituary, April 26, 2003

The Nobel Museum 2003 The Sydney Morning Herald

The Times, obituary April 28, 2003

Brain & Mind magazine, April-July 2003

VITAL STATISTICS

Name: Bernard Katz

Born: Leipzig

Birthdate: March 26 1911

Died: April 23 2003 in London

School: König Albert Gymnasium in Leipzig

University: University of Leipzig: University College, London

Married: Marguerite Penly in 1845 in Australia; widowed 1999

Children: Two sons, David and Jonathan

Liver: Although naturalised as an Australian citizen in 1941, he retured to live in London in 1946 where, after his retirement in 1974, he remained active in research council and science administration

AWARDS AND ACCOLADES

1933: Siegfriend Garten Prize for physiological research

1939: Beit Memorial Research Fellowship

1952: Fellow of the Royal Society

1961: Fellow of the University College, London

1965: Feldberg Foundation Award

1967: Baly Medal, Copley Medal

1968: Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians

1969: Awarded a British Knighthood; Foreign Member of the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters; Academia Nazionale Lincei; American Academy of Arts and Sciences

1970: Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

Katz’s publications included Electric Excitation of Nerve (1939), the classic text Nerve Muscle and Synapse (1966) and the widely read and admired, The Release of Neural Transmitter Substances (1969).

WHY HE WAS AWARDED THE NOBEL PRIZE

Katz was renowned for his work on nerve biochemistry and the pineal gland. He shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Ulf von Euler of Sweden and Julius Axelrod of the United States.

Katz uncovered fundamental properties of synapses, the junctions across which nerve cells signal each other and to other types of cells. He was especially interested in the electrical events that occur when impulses in motor nerves induce muscle activity by acting at motor end-plates. These special structures in the muscle, with condenser-like properties, are charged by nerve impulses and their discharge in turn activates the muscle.

Through the discovery of the existence of “miniature end-plate potentials” Katz demonstrated that the messenger substance between the motor nerve and the muscle end-plates, acetylcholine, was released from the nerve terminals in small packages.

New substances for the treatment of high blood pressure and Parkinson’s disease are the results of an increasing understanding of the nature of mental disease and psychical disturbances.