Swallowing the ScienceBy Lia Timson

Swallowing the Science

By Lia Timson

J Robin Warren 1937 –

Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine 2005

Shared with Barry J Marshall

Barry J Marshall

1951-

Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine 2005

Shared with J Robin Warren

When accepted thinking suggests that a medical condition results from human behaviour, it takes courage, perseverance and insight to prove otherwise

When accepted thinking suggests that a medical condition results from human behaviour, it takes courage, perseverance and insight to prove otherwise

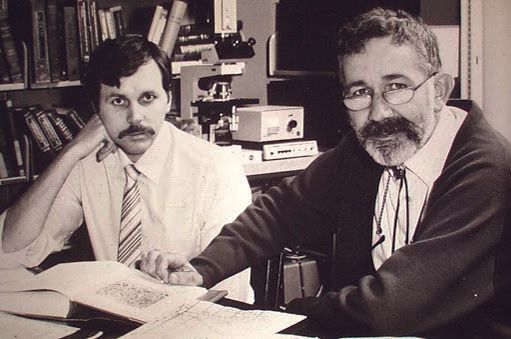

The discovery by doctors Barry Marshall and Robin Warren of the bacterium that causes stomach ulcers has led to new treatments and technologies.

Things might have improved for scientists since Galileo Galilei was put under house arrest for daring to challenge the wisdom of the day by asserting that the sun, not the earth, was at the centre of the universe. However, some pioneers still must expend time and effort to disprove the prevalent thinking in their field before their findings can be accepted.

This was so for two of Australia’s contemporary Nobel Laureates. Doctors Barry Marshall and Robin Warren went against widely accepted scientific belief when they proved stomach ulcers were caused by bacteria, not stress.

Their teamwork began in 1981 but it was only 24 years later that their subsequent breakthrough was recognised by the Karolinksa Institutet of Swedent, which awarded them the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 2005.

The discovery of the helicobacter pylori (Hp) bacterium and its role as a catalyst for the cure of the chronic, disabling, previously incurable peptic ulcer disease was described by the Institute as “remarkable and unexpected”.

It decreased the incidence of stomach cancers and later made ulcer surgery and years of stress treatment for gastritis redundant. Although half of the global population – higher in developing countries – carries the bacteria unknowingly, ulcer patients can now be treated with a short course of antibiotics. This alone is a result of the pair’s original work.

Their discovery and the ongoing research that ensued also gave birth to a whole new industry – as Dr Barry Marshall describes it – an entirely new discipline which employs hundreds of scientists worldwide among pathologists, researchers, those advancing the drugs and treatments for gastric diseases, and those working on technologies and vaccines enabled by it.

“We’re helicobacterologists,” Marshall says.

“There must be over 1,000 scientists who now make a living out of helicobacterology. We have a global conference each year and more than 400 people come to study the genome. In Australia alone we have four or five groups – some 20 people specialise in Hp outside my team.”

By the end of the 21st century’s first decade, scientists had expanded the pairs original discovery beyond peptic ulcers to include gastritis, duodenal and stomach cancers, among other sequelae. Marshall himself had furthered his studies to include using helicobacter pylori as a vaccine vehicle to prevent diseases as diverse as flu, hepatitis and malaria, and to understand patterns of human migration through the DNA of Islander peoples.

GAINING FORMAL ACCEPTANCE

So why did it take so long for helicobacter pylori to gain formal acceptance? This question is often asked of Robin Warren, now retired except for the multitude of Nobel-related speaking engagements he commands every year. "One of the difficulties when I started was that the standard medical teaching for a century was that the stomach was sterile. Bacteria didn't grow there," says Warren. "It was just like the earth being flat. It was a fact. The medical establishment is conservative and doesn't like sudden changes." While the duo is credited with the discovery of the helix-shaped bacterium in 1982, it was Warren's first observations as a young pathologist in the Royal Perth Hospital in Western Australia (WA) that gave rise to their partnership. "I found them in one case in 1979 a couple of years before I met Barry," he says. "I'm a pathologist. I look at pieces of tissue, trying to work out what's wrong with them for the surgeons who send them down (to the lab). One of the pieces of tissue was a piece of gastric mucosa from the stomach and I thought I could see a lot of bacteria on the surface, so I stained it with a special stain that shows the bacteria very nicely. I hadn't seen bacteria before in the stomach and no-one knew of any reports of them. So I kept looking and I kept finding more and more and eventually I was finding them in a third of the biopsies." In 1983, in a letter to The Lancet medical journal, Warren summarised his initial findings. In a separate letter Marshall detailed the work they were beginning together. The following year the journal published a co-authored article with detailed proof of their discovery. That is the one Warren believes won them the Nobel Prize two decades later. "Barry first suggested sometime after we published our article (that we may win). I told him not to be so bloody silly," Warren laughs. "When I heard I got a bit of a shock actually," he said after news of the prize. Although the first step in scientific recognition had taken place with the published articles, the young medicos experienced great difficulty convincing their peers. Warren later told a gathering of doctors in Stockholm, Sweden: "I was unable to convince the commissioning (doctors) of the importance of the organisms. While histology suggested the opposite to me, it was hard to prove. I worked in a laboratory without patient contact. I couldn't obtain the biopsies I wanted and the idea of taking biopsies to culture was not considered to be in the patient's interest." Things changed when Marshall, then a young registrar in gastroenterology at the same hospital, took an interest. "Someone suggested he come down and see that crazy pathologist who was trying to suggest bacteria cause gastroenteritis. He burst into my office one day without knocking and demanded to see my work. He was quite a wild young man," remembers Warren who is 14 years Marshall's senior. "He was the first person to actually show an interest so I was quite happy to show it to him."

Marshall's curiosity was unusual among doctors at the time, but natural for him as it stemmed from his blissful ignorance of specialist doctrine. "Clearly this was an interesting thing to study ... but I may have had other advantages compared with colleagues Robin had approached previously," he wrote in an autobiographical article for the Karolinska Instituter. "I wasn't coming from a background in gastroenterology, so my knowledge and ideas were founded in general medical basic science rather than the dogma one was required to learn in specialist medicine." Marshall was indeed required by the hospital to perform a different clinical research project each year as part of his medical training. This pleased him greatly as since childhood he had maintained an open mind towards scientific experiments - from homemade explosives and a hydrogen generator for balloons, to making a diagnostic of poisoning while attempting to perform cardio-pulmonary resuscitation at the age of 12 on his 18-month-old sister who had ingested kerosene but was, he admits, still breathing. (The feat earned him his first newspaper mention the next day.) At Royal Perth Hospital he was interested in 'various projects, including being "engrossed in a study of heat stroke in fun runners". This could have led him to a sports or environment medicine specialisation, but instead his boss suggested the gastroenterology project. He was told about Warren's suspicions about a bacterial cause of stomach inflammation and about his list of hospital patients with bacteria present in their stomach biopsies. Lab-bound Warren needed a doctor who could move through the hospital following up those patients. "I was especially interested because one of the patients on Robin's list was a woman I had seen in my ward, who had severe stomach pain but no diagnosis. In desperation we had referred her to a psychiatrist and commenced antidepressant medication for want of a better treatment," Marshall wrote. He agreed to send Warren a number of biopsies to see if the findings could be replicated. "They were. So he became more enthusiastic and we became collaborators.

Barry was the only person who believed me at all for about five years," Warren says, although he credits his late wife, Winifred, a general practitioner and psychiatrist, with supporting and encouraging his research until her death in 1997. Together, Marshall and Warren studied a further 100 patients as well as Marshall himself who drank a glass of helicobacter pylori and consequently suffered from a two-week bout of gastritis. While being a volunteer guinea pig is used intermittently by scientists today despite being frowned upon, at the time there were compelling reasons for the experiment. Not the least, the need for proof. "In retrospect my experiment could've gone wrong," says Marshall, professor of microbiology and immunology at the School of Biomedical, Biomolecular and Chemical Sciences at the University of Western Australia since 1999. But the excitement of the discovery and the possibility - however remote - of a Nobel Prize were good incentives. "The Nobel Prize helps innovation because it helps create a parallel scenario. Someone young on a low salary, slaving away on weekends trying something new, everyone says he's a fool, but he says 'just wait till I get the Nobel Prize'. I can't say I was really like that, but it helps. It's like the Olympics for science," says Marshall. The pair received a number of prestigious prizes on the way to the Nobel, each with its own benefits and small monetary reward. From their first joint recognition - the Warren Alpert Prize from the Harvard Medical School in 1994- to the medal of the University of Hiroshima for Warren and the Benjamin Franklin Medal for Life Sciences for Marshall, their lives have been peppered with accolades. In 2007 they were appointed Companion of the Order of Australia. But it was the Nobel Prize that finally engraved their names in the world's hall of fame and gave them license to spend a little. They each received a slice of the 2005 Nobel total prize pool of 10 million Swedish kronos or approximately 1 million euros at the time. "It's good I can share with the family, take them to Sweden. It's much better value to know that I can temporarily afford to board the dog for $30 a day while we're away," Marshall laughs. Seriously speaking, Marshall is pleased the prize did not come earlier in his career as he feels better prepared now for the notoriety that followed such an honour. He is often asked if he has any regrets, especially with regards to not having patented an antibiotic treatment for ulcer treatment - pharmaceutical companies today earn a steady income from such drugs. Despite not having a crystal ball, he quips, "it turned out alright in the end". "If I had had a good patent lawyer, I could've done it. But I could've made a lot of money," he says only half-jokingly. "Life would've been pretty strange (with money). I've had a very interesting life, I wouldn't change that."

SEMINAL INFLUENCES

Barry Marshall was the oldest of four siblings, born into a mining community in the WA town of Kalgoorlie, on September 30 1951. His early childhood memories are peppered with enterprising boys' adventures made possible by the world around him. He played on the beach near their first Babbage Island home, across from the whaling station at Carnavon where his father Bob worked in the mining trades. Later, alongside his brothers, Barry concocted homemade engines and electromagnets from scrap metal, and experimented with explosives made with pharmacy chemicals. His interests always involved scientific pursuits - be they of medicine, physics, chemistry or mathematics. His mother, Marjory, was a nurse and it was with her that as a young medical student Marshall had his first medical arguments. His earliest source of medicine information was her copy of the Modern Medical Counsellor- A Practical Guide to Health (1955). He later purchased his own copy at a second-hand bookshop. It sits proudly on his office shelf. "We used to have a lot of arguments about what was really true in medicine. She would know things because they were folklore and I would say, 'That's old-fashioned. There's no basis for it, in fact.' - 'Yes, but people have been doing it for hundreds of years, Barry, therefore there must be some use in it. That can be true," he recounted in an interview to the Australian Academy of Science. It was Marjory's higher education aspirations that took the family away from the mining environs to the state's capital, Perth. Marshall believes she did not want her children following the locals down the mine shaft, as well-paid as the trade was. She wished for them to study and enter a profession instead. His rational choice to study medicine had less to do with medicine itself and more with not pursuing mathematics, which he loved but found the daily calculus boring.

Robin Warren also pursued medicine after being influenced in part by his family. His mother, Helen, was also a nurse and her father, Sydney Verco, one of a long line of prominent Verco doctors - a family name that still adorns many a surgery door and hospital ward in South Australia (SA). Warren was born on June 11 1937, in North Adelaide, SA - a member of a fifth generation of free Scottish settlers who commanded vast tracks of outback land for cattle and wheat production. His father, John Roger Warren, later became a leading Australian winemaker co-producing Hardy's Cabinet Claret, a top selling drop credited with changing Australia's wine drinking habits. After his grandfather's death and the difficult financial situation that followed, his mother was unable to pursue her aim of becoming a doctor like her father and her brother, Luke. She trained as a nurse instead. "I cannot remember my mother ever pressuring me to study medicine, but somehow this always seemed to be my aim," he said in his autobiographical article. He defied earlier doctor recommendations to avoid medicine - he had suffered from grand mal epilepsy at 16 and was considered not fit enough to pursue medical school - to follow his calling. His main inspiration was Luke Verco who became a captain in the Army Medical Corps during World War II and later a country general practitioner. Coincidences between Marshall and Warren do not stop at both their mothers being nurses, or their early passion for mathematics and for varied medical disciplines (Warren enjoyed botany and zoology, while Marshall liked biology and biochemistry). Both married women in related fields (Warren's wife Wini was a psychiatrist, Marshall's wife Adrienne a psychologist) and fathered girls who, after earlier career choices in law and design, respectively, changed course to follow in their fathers' footsteps, pursuing medicine.

A LEAP IN FIVE YEARS

Marshall does not believe things should be named after people until they are dead- "in case they become less reputable" - but he has made an exception for the institution that now bears his name. The Marshall Centre for Infectious Diseases Research and Training housed in the University of WA's Faculty of Life Sciences was funded to the tune of $4 million by the Federal Government at its inception. Ever the entrepreneur, he quickly recognised the publicity value of the obel accolade and of his own newly found fame. "It's a way to create extra value and some free publicity for the university. I was happy to do it because the people who now spend time in the lab, the postgraduate students, they also get the Nobel Prize prestige on their CV. no matter how dis-reputed I get, they can't take the Nobel Prize off me," he jokes. It is but one of the many consequences arising from professor Marshall and now emeritus professor Robin Warren's receipt of the Nobel Prize. The Marshall centre is the focal point for postgraduate studies into infectious diseases, a laboratory for innovative thinking in biotechnology and a poster-child for scientific advancement in WA and the country as a whole. Marshall is also thankful for the doors the prize of prizes has opened - "we now go straight to the top of government or academia" - particularly as he has spent years working to attract funding for other helicobacter projects. The Laureates also count with full-time help of dedicated staff members at the Office of the Nobel Laureates who manage their prize-related engagements including guest-speaking appearances, overseas travel and those endless requests for autographed photographs, which Warren finds obsequious, from every corner of the world. "I still get a lot of requests for autographed pictures," Warren says, "from places like India and Poland. Some are so deferential, it's like they are bowing. It's quite strange. [Their requests] sound like they've got me up further than God. I'm sure I'm nor anything like that." Perhaps the biggest progress since the awards night on December 10 2005, has been the private and government funding that Ondek has attracted.

Someone young on a low salary, slaving away on weekends trying something new, everyone says he's a fool, but he says 1just wait till I get the Nobel Prize'. I [Marshall] can't say I was really like that, but it helps.

The company, set up by Marshall, won raising capital for the development and possible commercialisation of an ulcer vaccine before the prize. Marshall was once frustrated at the lack of Australian investors who understood the high-risk-highreturn nature of science subsidy. He says the mining sector seemed to be able to test the ground anywhere and immediately attract funding, whereas biotechnology research was met with suspicion by private and public investors. Thanks to the prize, however, that is no longer the case. Ondek chairman Peter Hammond says there was a leap in confidence among investors after the announcement. In the subsequent two years, the company attracted AUD2.6 million Australian dollars in private funding and another matching $2.38 million from the now defunct Federal Commercial Ready grant. "The prize has been a great help in attracting investment. Investors now realise there are top scientists like Barry in Australia and that we need to support them to keep them here," says Hammond. "We're even turning around the brain drain," Hammond says of Alma Fulurija, an Australian scientist who returned from Switzerland to join the company. Interestingly, it was the mining industry, which had lost Marshall to medicine, that put up the first fist-full of cash for Ondek along with Swedish investors. Hammond says it is a perfect fit. "These investors understand the risk profiles. Mining is not that different to science, they 'roo have to go through a long research phase before commercialisation. Also, they know they have to build alternative industries in WA. We won't be able to mine iron ore forever. They see biotechnology as an industry where Australia has a competitive edge, not dissimilar to the edge they have in mining." Although Hammond says the company was always going to be able to raise some funds, the Nobel Prize fast-tracked the process considerably. It has also helped attract the right people to the team. "We're not having trouble at all attracting the right people because we're not doing it on the cheap with remuneration," says Marshall. The money is used to fund Ondek and its team of 15 renowned scientists from Australia, Korea, China, Sweden, the United States and Switzerland. New rounds of funding begin every January to guarantee the group's future. In 2010 the company raised $10 million to continue human trials of a vaccine made using helicobacter as irs vector. The first experiment, involving 36 patients in Perth, concluded in June 2011 and proved a safety profile for the bacteria which survives stomach acids to live in its host long enough to inoculate them against illnesses. Ondek will now move to see approval to conduct another trial, this time with a flu virus antigen attached to the bacteria. The company's initial aim is to find an oral form of vaccine (in food, drink or capsule) for the common flu and later, possibly, hepatitis. The company says the approach could help fight other diseases and even be used in hormone therapy.

EXPERIENCE BRINGS CONFIDENCE

It has been almost 40 years since Marshall and Warren embarked on their helicobacter journey. Marshall is still the world authority on the subject. He continues to work on expanding his knowledge of the bacterium and to practise as a gastroenterologist for rare, difficult-to-manage helicobacter infection cases at the Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital in Perth. In a fast-paced world where young people constantly change jobs and career directions citing boredom or slow upwards progress as reasons, I asked Marshall what it is like to dedicate your life to the pursuit of one subject. "It does give you confidence," he laughs. "Some things need time and resources to develop. It would be wasteful to do something on a small scale and stop half-way through it." If Marshall and his team succeed in mass producing vaccines using Hp as vector and helping treat debilitating diseases in developing countries, his one-track career will have paid off. "The fact that we haven't changed direction at all is a plus," he concludes while still seeing the world through an Hp-laden Petri dish. His latest co-authored paper is titled 'The Peopling of the Pacific from a Bacterial Perspective'. It is a colla bora rive study of the different strains of helicobacter present in the DNA of Islander peoples and their ability to suggest patterns in early indigenous migration. His life's work has also made him less stressed and too busy to sweat the small stuff. "I lost my licence, so I don't speed anymore. I just arrive late now," he says. Marshall continues to maintain a broad range of interests outside the lab. He fiddles with computer programming (something he used in the early days to harness stomach ulcer data from doctors around the world), is an iPad devotee and a fan of social networking. He is on Twitter, maintains a casual blog, is on Facebook with Robin Warren and is permanently curious about the world and digital technologies around us. He is a fan of Apple, the company, and even expressed regret at not contacting its former chief executive, Steve Jobs, before he died. "I wish I had sent Steve a card. Next time I think of something kind to do I won't delay. let's cure pancreatic cancer. #thankyousteve," he tweeted on October 6 2011. He even doubts the privacy-zealous when it comes to the internet, saying he does not care about others finding out about him online. "If everybody just says what they are doing, the amalgamation of information can let us see what's happening. I'm less and less concerned about security. In fact I'm running a mini campaign against it."

THE FUTURE

Dr Marshall will remain at the helm of both the Marshall Centre and Ondek's plans while also lecturing at the University of Western Australia and travelling around the world to further the vaccine cause.

He wants to realise his dream of an unobtrusive, painless vaccine that can be self-administered. "People don't like to have injections. If we had an edible product available in the supermarket, no one would prefer an injection," says Marshall. "But the really exciting part of this project is to be able to vaccinate easily and cheaply millions of people, say, against malaria with live bacteria." A collaborative agreement with the Japanese giant laboratory that produces and sells the fermented lactobacillus drink Yakult was signed in 2008 but has not progressed to Marshall's aim of a liquid h. pylori drink available at the check-out. However, he has not abandoned the thought of an ingestible vaccine. "It's not a fancy concept. We know we can make it work on mice with helicobacter diluted in water. So ideally it will be a freeze-dried version put in a capsule and available on the pharmacy shelf." Robin Warren, although only a happy external observer, is fully aware of the repercussions his initial discovery can still have on the state of the world's health. "I think [the ingestible vaccine] is a very clever idea. I hope it comes off. h. pylori is the perfect bacteria to do it with because it sits in the stomach. If you infect the stomach with a harmless variety of these bacteria, they will keep on producing antibodies," says Warren. The septuagenarian is happy to have been pulled out of retirement by the numerous Nobel Laureate speaking engagements that now see him globetrotting from Taiwan and Thailand to Rome and Greece, but he is trying to keep the overseas trips to a manageable few a year and he is not tempted- not even a little bit- to don his lab coat again. "I've avoided doing as much as Barry has. His work is ongoing. He needs the constant publicity to get the finance to help run the centre. I have plenty of other things to do and the work they are doing now is way beyond the stuff I used to do," he says. He likes to dedicate time to photography - a hobby pursued since his teenage years - and to his growing brood- at time of writing Warren had seven grandchildren and four great-grandchildren whom he loves to photograph. While he has no regrets, widowed Warren would have liked to replace his beloved 18-year-old canine companion who died in 2007. But like the work in the lab, a puppy, too, is out of the question. "I would like to get another one, but all this travelling has kept me out of getting a dog. I couldn't leave a puppy behind," he says. "Actually, that's the one thing about the Nobel Prize I don't like."

Vital Statistics:

Name: John Robin Warren

Born: North Adelaide, South Australia

Birthdate: June 11 1937

School: St Peter’s College (Adelaide)

University: University of Adelaide

Married: Dr. Winifred Theresa Williams, 1962, Winifred died in 1997

Children: John, David, Patrick, Andrew and Rebecca

Lived: Mainly in Adelaide, SA, and Perth, WA

AWARDS AND ACCOLADES:

1994: Warren Alpert Prize (shared with Marshall)

1995: Australian Medical Association (WA Branch) Medical award (shared with Marshall)

1995: Distinguished Fellows Award, Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia

1996: Inaugural Award, The First Western Pacific helicobacter Congress

1996: The medal of the University of Hiroshima

1997: Paul Ehrlich Prize (shared with Marshall)

1997: MDhc, University of Western Australia

1998: Centeneray Florey Medal, Australian Institute of Political Science (shared with Marshall)

2005: The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (shared with Marshall)

VITAL STATISTICS:

Name: Barry James Marshall

Born: Kalgoorlie, Western Australia

Birthdate: September 30 1951

School: Newman College (Perth)

University: University of Western Australia

Married: Adrienne Feldman in 1972

Children: Luke, Bronwyn, Caroline and Jessica

Lived: Mainly Perth, WA, and Virginia, United States

AWARDS AND ACCOLADES

1994: Warren Alpert Prize (shared with Warren)

1995: Australian Medical Association Award (shared with Warren)

1995: Albert Lasker Award

1996: Gairdner Award

1997: Paul Ehrlich Prize (shared with Warren)

1998: Dr AH Heineken Prize for Medicine, Amsterdam

1998: Centenary Florey Medal, Australian Institute of Political Science (shared with Warren)

1998: Buchanan Medal, Royal Society

1999: Benjamin Franklin Medal for Life Sciences, Philadelphia

2002: Keio Medical Science Prize

2003: Australian Centenary Medal

2005: The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (shared with Warren)

2007: Companion of the Order of Australia

2015: Fellow of the Australian Academy of Health and Medical Sciences

Why they were awarded the Nobel Prize

Barry Marshall and Robin Warren were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2005 for their discovery of the bacterium helicobacter pylori and its role in gastritis and peptic ulcer disease. Previoulsy it was believed stomach ulcers were caused by stress. Doctors Warren and Marshall proved bacteria can live in the stomach despite its acid environment. Although millions of people around the world carry the bacterium in their stomach naturally, those suffering from ulcers and other gastric diseases are now routinely treated with antibiotics. Marshall later patented diagnostic tests, the CLOtest (mucosa biopsy) and PYTest (breath) to detect helicobacter pylori. These are still in use today.