CHICKEN AND EGG: UNDERSTANDING IMMUNITY

CHICKEN AND EGG: UNDERSTANDING IMMUNITY

Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet’s study of viruses formed our concept of understanding ofimmunity that has become vital in today’s field of organ transplants.

Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet’s study of viruses formed our concept of understanding of

immunity that has become vital in today’s field of organ transplants.

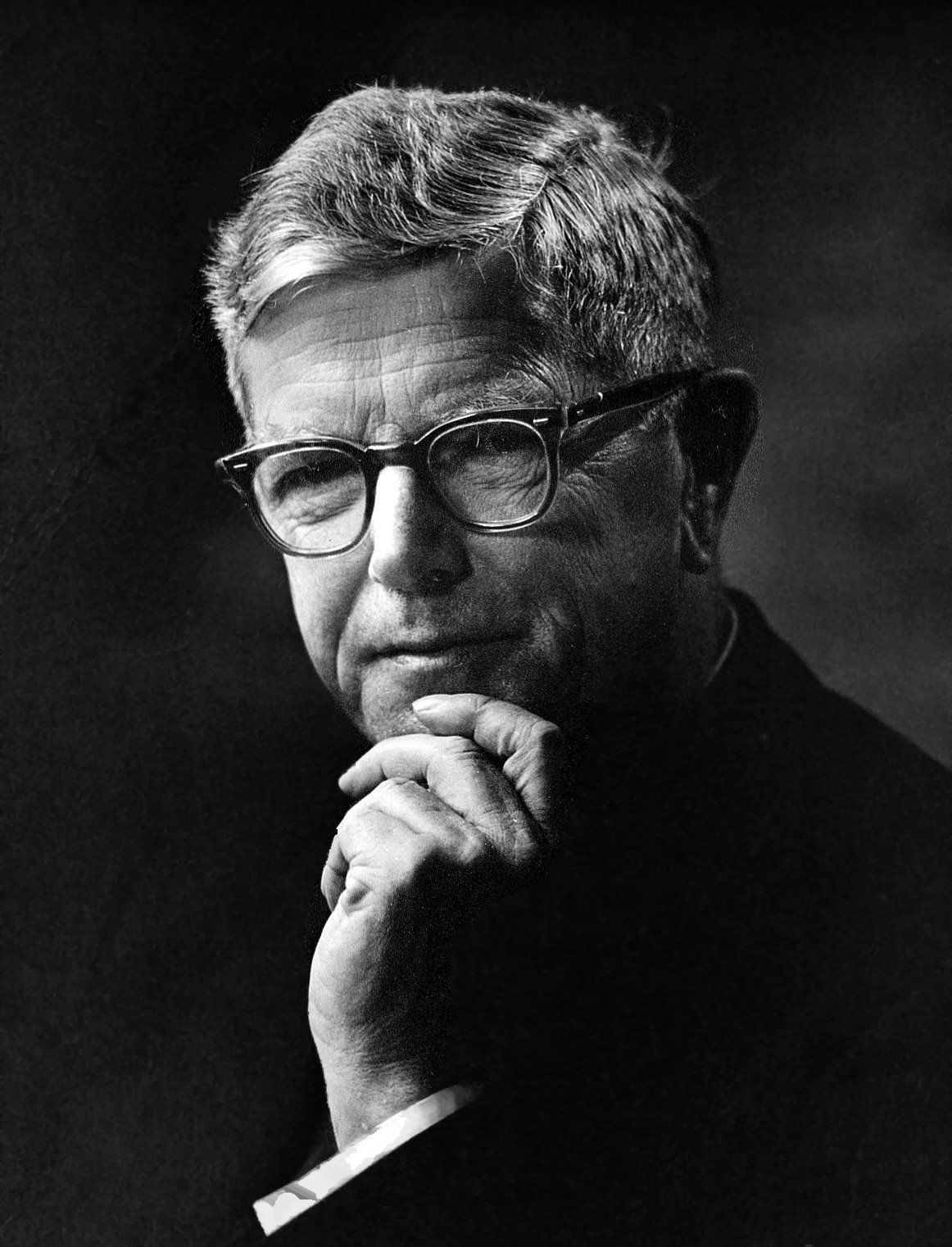

Frank Macfarlane Burnet 1899-1985 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine 1960 - Shared with Peter Brian Medawar

Once injecting himself with a deadly virus to prove a point , it was Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet’s practical, hands on approach to science that made his breakthrough work possible

Once injecting himself with a deadly virus to prove a point , it was Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet’s practical, hands on approach to science that made his breakthrough work possible

In was Christmas 1950, when an unusually warm, wet weather front moved across the Murray Valley in northern Victoria and created ideal conditions for an explosion in mosquito numbers. Within days, the surrounding farmland was strewn with dying rabbits. Scientists, by luck, had discovered the carrier needed to spread the myxoma virus they had developed and had been trying for years to use on the country's devastating rabbit plague. Until now it had been assumed the virus could only spread very slowly by direct contact among rabbits. However, the humid conditions combined with the mosquitoes revealed there was a highly effective natural carrier after all. Farmers, whose landscapes and livelihoods were being destroyed, were ecstatic. But their jubilation quickly turned to horror. People also began to fall ill and die from a deadly new brain disease. The media quickly blamed the new rabbit virus and the scientists who had unleashed it. Virologists knew that myxoma, which causes myxomatosis in rabbits, had no effect on humans, but were struggling to be heard or seen in the outcry and hubbub of "Death Valley" headlines. Something or someone was needed to calm a panicking population - someone who was not only eminent in medicine but who was also respected and trusted by the community. The man the government turned to was noted virologist Dr Frank Macfarlane Burnet, director of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute in Melbourne. Burnet, known to friends and colleagues by his childhood nickname "Mac", decided the best way to calm everyone was to simply inject himself with a large dose of the myxoma virus and show people, in the most dramatic way possible, that the deadly new human disease - Murray Valley encephalitis - was not myxomatosis. After some discussion it was decided that both Burnet and an associate, Frank Fenner (who would later achieve world renown for his part in eradicating smallpox from the planet), would inject each other. Fenner had just been appointed as a professor of microbiology at the John Curtin School of Medicine at the Australian National University in Canberra and was working at the Institute until his new laboratories were built. By chance, he and Burnet were working side by side. Fenner was filling in time by studying the myxoma virus and Burnet on the mystery virus that was killing people.

HUMAN GUINEA PIGS

Burnet prepared a compound containing the myxoma virus - a dose 100 times greater than a rabbit or human would receive from a mosquito: "He injected me and I injected him," recalled Fenner, who, with scientist Francis Ratcliffe of the CSIRO (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation), later wrote the definitive textbook Myxomatosis. Just after the pair had finished injecting themselves, CSIRO head, Ian Clunies Ross, walked in demanding that since myxomatosis was a CSIRO project, he should also be injected. This was done and after three weeks when all tests showed the scientists were free of any myxoma antibodies (as they knew would be the case), the myxomatosis scare faded into history. What did not fade, however, was the lasting impression in the public's mind of the scientists' perceived bravery. In becoming human guinea pigs, Burnet, Fenner and Clunies Ross had perpetuated an important, although fading tradition, in which scientists take the unknown risks as the first volunteers in their experiments. Meanwhile, the mystery human virus was identified as a new strain of encephalitis, triggered by the same warm, wet weather that got myxomatosis off to a flying start. Murray Valley encephalitis, in which Burnet became the world authority, remains to this day.

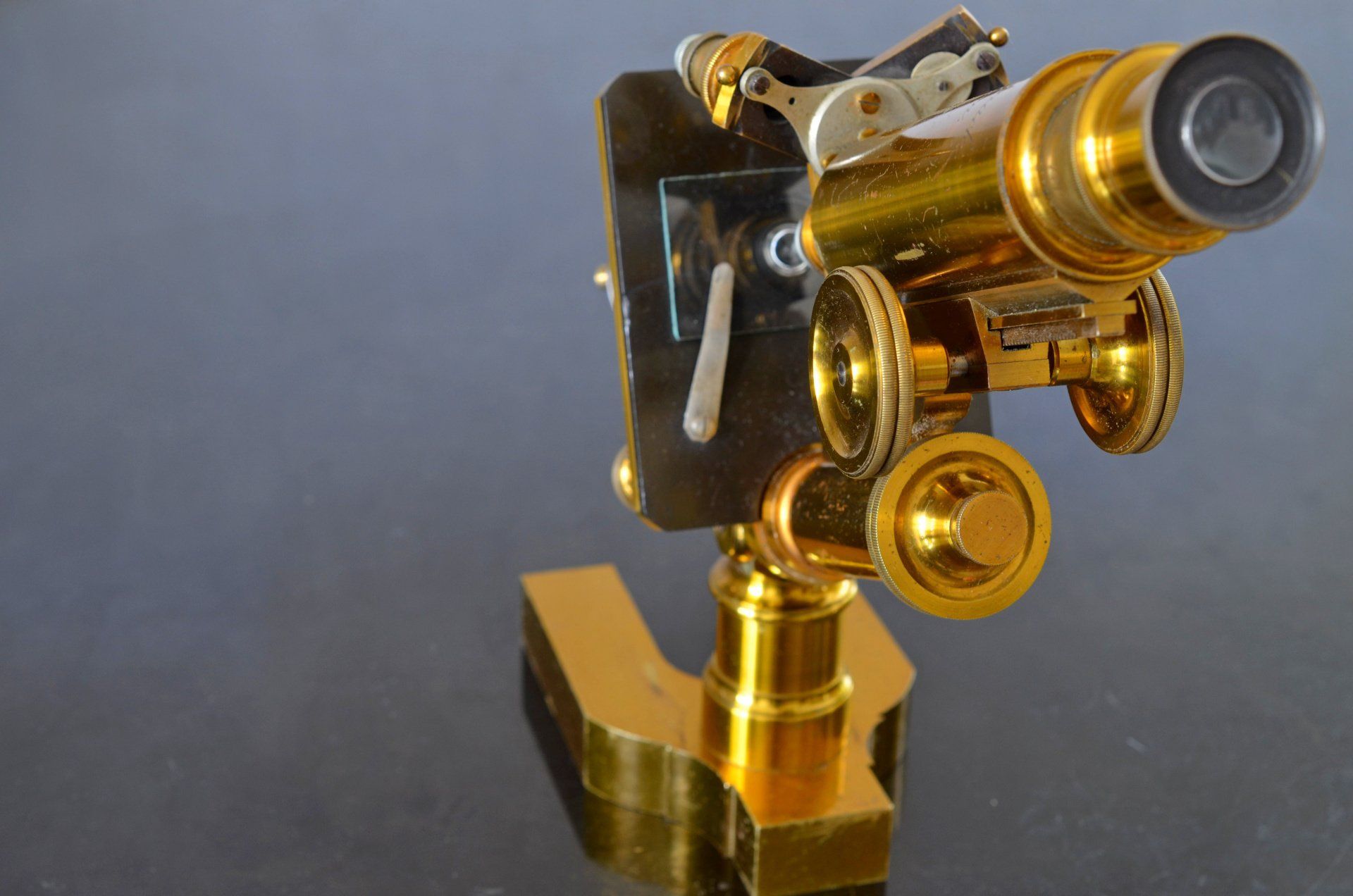

The approach to the myxomatosis scare typified Burnet's practical, sleeves-up attitude. In much the same manner as Pasteur, Burnet was committed to tackling practical problems. He displayed that same practical attitude in his momentous decision, a few years after the myxoma episode, to move away from virology and concentrate on immunology - the decision that culminated in him winning the Nobel Prize in 1960. By the mid-1950s, Burnet had realised that the nature of virology research was changing: modern laboratories were turning to the new fields of molecular biology and DNA coding. Against this, Burnet's main research tools- a chicken egg (literally) and a microscope - looked old-fashioned. Throughout his career, Burnet favoured an experimental technique developed while working at the National Institute of Medical Research in London in the 1930s.

An opening was made in the shell of an egg' and a virus sample was injected into the membrane that surrounded the chick embryo. In these conditions most viruses multiplied, allowing closer study. Yet rather than learn new methods - such as the use of tissue culture - in virology, in which he had already achieved acclaim, Burnet decided to move on. He had always been interested in immunology and he now directed his own and the Institute's work into this area. While the radical change in direction was later justified with the awarding of the Nobel Prize, others felt Burnet's move was dictatorial. Gustav Nossal, who would eventually succeed Burnet as director of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, arrived at the Institute in 1957 expecting to work on viruses. He was reportedly taken aback when told of the change in direction. For a man regarded as one of the great scientific thinkers of the 20th century,

Burnet's propensity for gloomy - often wrong - predictions about science, especially after his formal retirement in 1965, often puzzled associates.

Professor Jim Goding of Monash University's Department of Pathology and Immunology recalls: "On the occasions that I got to know Burnet socially, I challenged him concerning his predictions. When confronted with the spectacular progress since his predictions, he would say, 'I stand corrected', but then immediately reiterate his belief that most of the really important work had been done and our generation was just tidying up loose ends." Nossal believed Burnet's stance simply reflected "the real pain that he felt in having to leave the scene of discovery". It showed one of Australia's greatest heroes as being very human. Innumerable records and memoirs tell the story of Frank Macfarlane Burnet. He was born in the Gippsland town of Traralgon on September 3 1899, the second of seven children. His father, also Frank, was the branch manager of the Colonial Bank and had emigrated from Langholm, Scotland, in 1880. In 1893, he married Hadassah Pollock Mackay, the daughter of a local school teacher, George Mackay, who had also emigrated from Scotland. From the time he was old enough to run around the district, which was still lush with bushland, the young Burnet revealed a fascination for biology, assiduously compiling the usual boyhood collections of butterflies, birds' eggs, rocks and beetles. His interest in the natural world became even more marked at 10, when his family moved to Terang in western Victoria, where the wildlife around Lake Terang was a source of unlimited discovery. Those who have written monologues and memoirs on Burnet's life, including his friend and colleague Frank Fenner, discovered the adolescent Burnet fitted a familiar profile of boys who were later drawn to an academic career. They were shy, socially late-maturing and had a strong devotion to their hobbies.

BEETLE MANIA

In Burnet's case, his passion from childhood was beetles, which he began to record and draw. He read all the biological sections of an old Chambers Encyclopaedia published in the 1860s, which introduced him to Charles Darwin. He wrote to Melbourne for a book about beetles, and was sent a translation of Fabre's Souvenirs Entomologique. Later he acquired Froggatt's Australian Insects, and covered its pages with his own entries on beetle collecting. His keen interest prompted the local Presbyterian minister to encourage his parents to send Burnet to university.

He was sent to Geelong College for four years - an experience he later revealed was not a particularly happy one - but in his final year he gained a scholarship to Ormond College, at the University of Melbourne. There he pursued medicine, mainly because it appealed to him more than what seemed to be his only other career options - law or the church. Fenner wrote that Burnet's early years at university were accompanied by wide reading and a broadening of horizons, and an evaluation of his ideas on religion. Despite growing up in a Presbyterian household in which church every Sunday was an unbending ritual, he soon became agnostic. Darwin's writings on evolution strongly influenced his early scientific work, while the incisive work of writer HG Well~ helped form his views on society. At the end of a medical course that was shortened to five years because of World War I and the perceived need to produce graduates quickly, Burnet graduated MB, BS (Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery) in April 1922, coming second in a class that contained four others who later achieved fame in science and medicine: Sir Roy Cameron (pathology), professor RA Willis (medical research), Dame Jean Macnamara (poliomyelitis research and campaigner for the introduction of myxomatosis) and Dame Kate Campbell (paediatrics).

After graduating, Burnet spent two years gaining his Doctor of Medicine, and then spent a year as resident medical officer in the Royal Melbourne Hospital. In the surgical wards, he came to know two eminent surgeons, Sir Alan Newton and Sir Victor Hurley, each of whom later served as a chairman on the board of WEHI while he was director.

However, it was while serving as house physician to Melbourne's leading physician at the time, the neurologist Dr RR (later Sir Richard) Stawell, that Burnet became convinced his future lay in clinical neurology. He applied for the post of medical registrar at Melbourne Hospital, intending it as a stepping stone, yet the medical superintendent had other ideas. Convinced that Burnet's introverted and awkward personality was more compatible with a career in a laboratory, the superintendent steered him into the job of pathology registrar and a few months later, senior resident pathologist. This became the start of his brilliant scientific career and his long association with the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute (the pathology laboratories of the hospital operated as part of the Institute).

In 1924, the Institute was given a fresh intellectual stimulus with the arrival from University College, London of Dr Charles Kellaway (later Sir Charles) who, as the Institute director, transformed it into a research facility specialising in physiology, biochemistry and bacteriology. Kellaway saw Burnet as the potential leader of the small bacteriology section bur decided he should first have overseas training. In 1925, Burnet left for England as a ship's surgeon. He took a paid position at the Lister Institute in London that still gave him time for research. Under the supervision of professor JG Ledingham, he gained a PhD from the University of London in 1928. Burnet's time in London was not all work and staring through a microscope. He returned to Australia in 1928 with his fiancé Linda Druce, an Australian who had been living in London. They married later that year on July 10 1928, and spent their honeymoon skiing at Mt Buffalo in northern Victoria. Yet it was another posting to London, this time to the National Institute of Medical Research at Hampstead in London in 1932-33, that changed the course of Burnet's scientific life. The post placed him in the thick of research that was opening up science's understanding of animal virology. During his visit, Burnet developed his work on the use of the chick embryo to study animal viruses. He also acquired a powerful friend in Sir Henry Dale, a pharmacologist and winner of the 1936 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, who offered him a permanent position at the National Institute. However, Burnet decided to return to Melbourne, where he became assistant director of WEHI, in charge of the virus section.

Back in Melbourne, Burnet continued to study the behaviour of a variety of viruses in the developing chick embryo. Seizing opportunities as they arose, he worked on psittacosis (parrot fever), carried out studies on poliovirus, and recognised a rickettsia (a micro-organism that resembled bacteria but can be as small as a virus and reproduces only inside a living cell) to be the cause of Q fever. Q fever, characterised by fever, chills, headache and weakness, is often mistaken for flu and is a zoonotic disease that spreads from animals, such as sheep, cattle and ticks, to people. The causative organism of Q fever was later named Coxiella burneti in Burnet's honour.

Pull out quote: Burnet decided to simply inject himself with a large dose of the myxoma virus and show everyone that the new deadly disease was not myxomatosis.

INFLUENZA INTEREST

However, his major interest from 1939 was the influenza virus, prompted by the discovery of methods of growing the virus in chick embryos. With the onset of World War II, his attention was focused on methods of immunising against influenza in case there was ever another pandemic like that of 1918-19, which killed more people than the whole of World War I. In 1942, he was offered a professorship at Harvard University in the United States and was strongly tempted, but he later explained that he felt a deep sense of loyalty towards the Institute and Australian science.

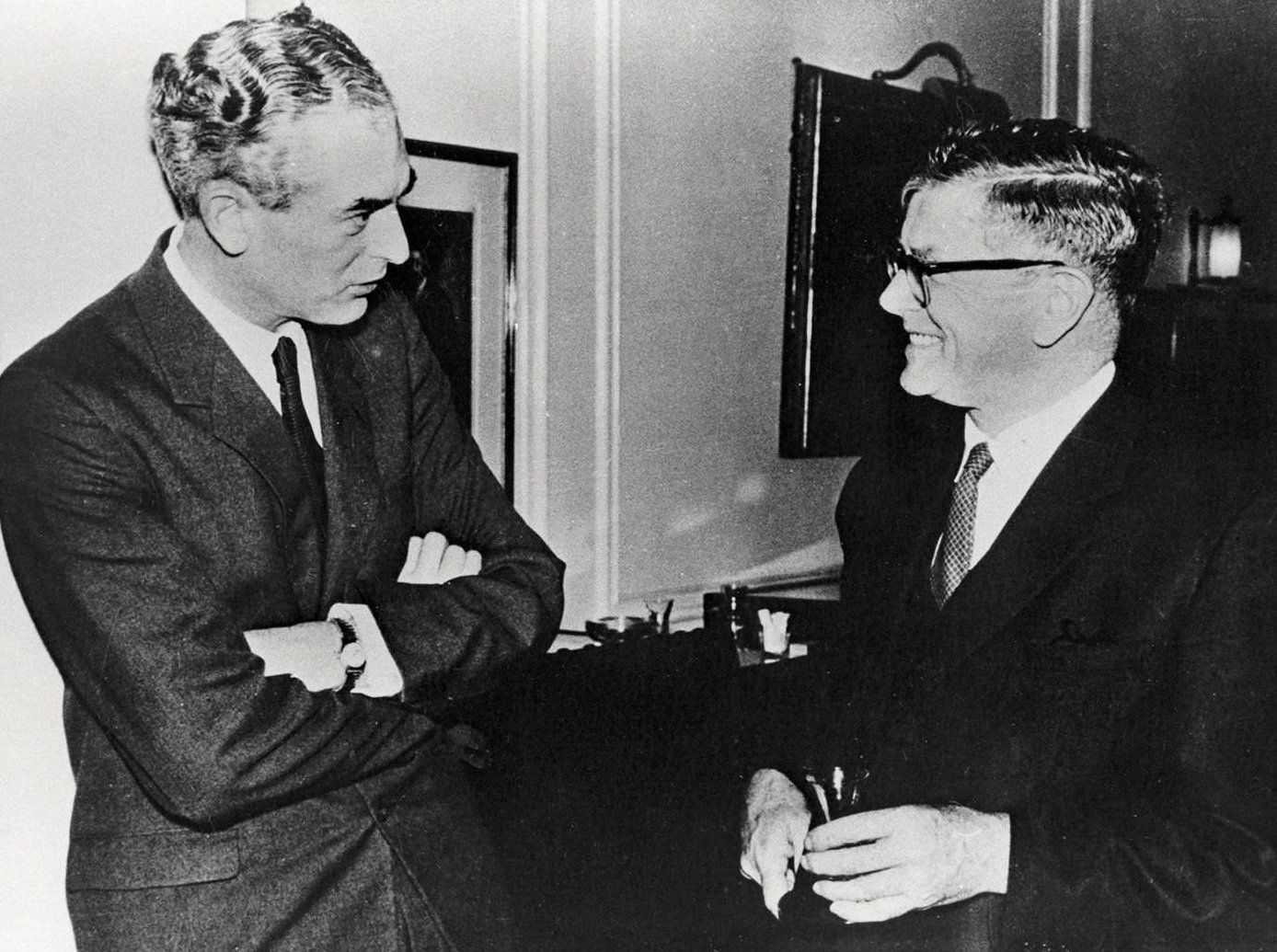

The patriotism he felt towards his country was reflected in the fact that many of his papers were first published in Australian scientific and medical journals. He even felt that it was an advantage for scientists to be relatively isolated in Australia, since it protected them from being too influenced by fashions in scientific thinking. In 1944, Burnet succeeded Kellaway as director of WEHI - even though Kellaway and Burnet himself had reservations about the appointment. Kellaway was worried that Burnet lacked the necessary leadership skills, and that the post might hinder Burnet's research work. The Institute's board overruled Kellaway, and Burnet immediately showed he was capable of making big decisions. He determined that the Institute should concentrate on animal virology, especially the influenza virus. His team was to eventually unravel the nature of the influenza viral enzyme (neuraminidase), which became the starting point for four decades of Australian research that culminated in 1999 with the release of the world's first anti-influenza drug, Relenza. During that time, because Burnet kept the Institute at the forefront of influenza research, it attracted numerous overseas scientists. Those who worked at the Institute had no doubt that they were privileged to be working with a man of genius. Burnet also had a reputation as a hands-on director. Until 1955, when he started travelling overseas more often and had to juggle increasing demands on his time, Burnet spent more than half of each day at the laboratory bench. He usually worked alone, sometimes joined by one or two graduate assistants and a couple of technicians. Few of Burnet's research papers list a co-author other than his graduate assistant of the day. Fenner says that Burnet was careful in selecting his graduate assistants - and the rollcall of highly competent women assistants (including his daughter Deborah) repaid him with many years of service. One, Patricia Lind, worked in the lab with Burnet from 1944 until his retirement in 1965. When Burnet and Medawar travelled to Sweden in 1960 to receive their Laureates, professor Bertil Lindblad, the president of the Royal Academy of Sciences, articulated their achievement during the award ceremony: "In your discovery of immunity produced in the embryonic stage and of actively acquired tolerance you have found a new biological law, opening up new vistas in experimental biology. The phenomenon of immunological tolerance which you have discovered will most certainly be of direct practical importance for the treatment of various kinds of injuries and diseases." During his time in Sweden to receive his Laureate, Burnet was clearly conscious of the historical significance of his achievement, and was keen to place it into a wider educational context. "I think that this occasion has a rather special significance for my own country, a middling small country a little bigger than Sweden but only now beginning to create an image of its own in the eyes of the world," he said. "Some day I hope that we will take our place along with Sweden as one of the centres where knowledge can do along with social progress to the good life we all seek." He then had a message for all students, not just those who might embark on scientific careers. "To advance science is highly honourable but other things are equally honourable. Perhaps when you are 20 to 30 years older, research as we know it may be less important than it is today but there will always be an obligation to pass on to the new generation the tradition of liberal scholarship. I hope that when you are as old as I am, skill and success in education will be as highly rewarded as success in scientific discovery is today. But whether your career is in research, in education, or in seeing that some of the wheels of our complex civilisation turn as they should, I wish you luck."

Although Burnet won the Nobel Prize for his work on acquired immunological tolerance, he was dismissive of its wider implications (one of his comments was quoted under the headline, "No great value in transplants, says top scientist"). Burnet considered his greatest contribution to biology to be his clonal selection theory. This theory, which sought to explain how animals could produce such a wide variety of antibodies, opened up vast new areas of research. However, it would take nearly another 20 years for the actual mechanism of clonal diversification to be discovered by Japanese immunologists Nobumichi Hozumi and Susumu Tonegawa, in 1976. Burnet had an unforgettable impact on the stream of scientists who came to The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, especially between 1944 and 1965. Although his management style could seem like a benign dictatorship, the Institute's scientists were granted many freedoms. Unlike others, Burnet did not put his name on papers to which he had not contributed. Highly animated discussions over morning and afternoon tea were a feature of Institute life. He read every paper from staff, scribbled clarifications over any points he felt were unclear, and returned the manuscript the following day.

RELUCTANT SPOKESPERSON

Burnet never courted interviews but he recognised the importance of talking to the media if the public were to understand the role of science and scientists. He would interrupt his precious time at the laboratory bench to take inquiries from the press and occasionally appear on television. After Burnet notionally retired in 1965 he broadened his interests even further, becoming a public commentator on issues as disparate as cigarette smoking and uranium exports. In 1966, he returned to the University of Melbourne where, over the next 12 years, he wrote 13 books on subjects ranging from immunology and human biology to ageing and cancer. He also produced a fourth edition of his first book, Biological Aspects of Infectious Disease. Most of Burnet's writings were not technical monographs, but written for the doctor or biologist who was not a specialist in virology, immunology or gerontology. Many of his popular books are highly readable. In 1973, Burnet's life was turned upside down when his wife Linda died of lymphoid leukaemia. She had been his companion on many of his overseas trips and when separated by distance, they had corresponded devotedly. Many of their letters are held at the University of Melbourne Archives, along with Burnet's photographs, diaries, notes, press clippings and early watercolours and sketches. After his wife's death, Burnet lived for a while at Ormond College at the University of Melbourne, which had been his home as a medical student. In was here that he renewed his friendship with the Master, Dr Davis McCaughey {later appointed Governor of Victoria). While devastated by his wife's death, Burnet was to find love again. In 1976 he married Hazel Jenkin, a widow who had endowed the library in the School of Microbiology to commemorate her only daughter Heather, who had died while a graduate student. In November 1984, Burnet was operated on for cancer and initially seemed to have made a good recovery, but secondary lesions were discovered in August 1985. As a biologist, Burnet accepted the inevitability of death and was impatient with proposals designed to prolong the life span. He had earlier recognised the scope for research "on the best means of minimising the depression and misery of pre-death", so it is perhaps fitting that he was spared those things. He remained mentally acute until he lost consciousness shortly after his last illness took hold. He died on August 31 1985, aged 86, at his son Ian's home at Port Fairy in Victoria, near where he had spent his early years. He was given a State funeral by the Federal Government, and was buried at Tower Hill Cemetery, near Port Fairy. His wife Lady Burnet survived him, along with his children from his first marriage, Ian, Elizabeth and Deborah, and eight grandchildren. Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet remains one of Australia's most acclaimed scientists; a man who made an extraordinary contribution to human medicine and wellbeing, and who also stood up as a proud Australian. Greatness became a mantel that he appeared to wear quite comfortably, yet at heart he did not move that far from the shy, curious child who used to wander through the bush, hunting down butterflies and drawing beetles in a sketch pad.

Vital Statistics

Name Frank Macfarlane Burnet

Born Traralgon, a small town in the industrial Latrobe Valley, Gippsland, south-eastern Victoria

Birthdate September 3 1899

Died August 31 1985, Port Fairy, Victoria

School Geelog College

University University of Melbourne; University of London

Married Edith Linda Marston Druce in 1928, widowed in 1973. Married Hazel Gertrude Jenkin in 1976

Children Three from his first marriage – Ian, Elizabeth and Deborah

Lived Mainly in Melbourne, but also in London

Awards and Accolades

1942 Fellow of the Royal Society of London

1946 Honorary doctorate from Cambridge

1947 Royal Medal, Royal Society of London

1948 Fellow of Royal Australasian College of Physicians

1951 Awarded a British knighthood

1953 Fellow of Royal College of Surgeons

1958 Order of Merit

1959 Copley Medal, Royal Society of London

1960 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

1960 Honorary doctorate from Harvard University

1961 Australian of the Year

1968 Honorary doctorates from Oxford and Monash universities

1978 Order of Australia

1981 Australian of the Year

Burnet was the most highly honoured scientist to work in Australia. Following his death in 1985, two Melbourne research units and an annual oration at the Australian Society of Immunology were named in his honour.

Why he was awarded the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prize was awarded with Sir Peter Brian Medawar of Great Britain for the discovery of acquired immunological tolerance. How does the human body recognise the difference between existing micro-organisms and dangerous invaders? This fundamental question worried away at Burnet during the 1940s. He studied every piece of literature he could find on the subject – and it was his ability to think laterally across all this information that produced the breakthrough hypothesis.

During Burnet’s study of influenza viruses in the 1930s and 1940s, he had developed methods for growing viruses in chicken embryos inside eggs. He noticed in his research that although normal hens could be infected with influenza and develop antibodies, chickens born from eggs with the virus did not develop antibodies when exposed to influenza. The chickens had an “acquired immunological tolerance” and did not raise an immune defence because their immune systems did not recognise the virus as foreign. This showed that when the immune system developed during the foetal stage, it recorded all proteins and micro-organisms in this enclosed environment as “self”, including the virus injected by the scientist.

Burnet’s theory was confirmed in experiments by English researcher Peter Medawar, and it was for their collaboration in developing a new understanding of the immune system that they were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1960. This understanding of the basis of immunity has become vital in the field of organ transplants. Prior to Burnet and Medawar’s work, it was thought that immunity was in some way related to the nature of an individual’s blood.