Dr Isaac Dzakpata is the Project Leader of Foundational Project 2.2, a recently commissioned study by the Cooperative Research Centre for Transformations in Mining Economies (CRC TiME), titled “Exploring the Issues in Mine Closure Planning”. He is also Work Area Leader at world-leading research organisation Mining3

Mine Closure Planning – A Complex Landscape Worthy of Exploration

Pioneering research and a brand new approach to management shine light on a complex issue. Can the mining industry and its various stakeholders, by aiming for exemplary results, re-imagine and redesign Mine Closure Planning as a recognised future discipline in time for Australia’s next mining boom?

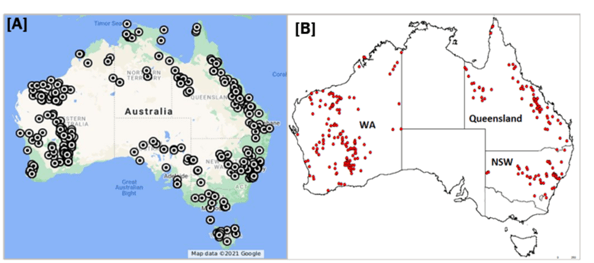

Mine planning (feasibility, production, or closure) involves effectively predicting the future (Brookwater, 2022), a challenge likened by world renowned management philosopher Peter Drucker to "driving along a country road at night with no lights while peering out the rear window." Mine closure planning (MCP) refers to the science and engineering aspects of envisioning and providing for the end state of a mining endeavour - a lifespan ranging from 5 to 70 years for new mines. Mining operators that have mismanaged closure historically have caused enormous harm and scarring to the natural environment. Australia is reported to have at least 60,000 abandoned mines (the majority of which are minor and the product of Australia's gold rush in the mid-1800s – before progressive rehabilitation became the standard).

The biggest challenge for MCP in Australia today centres on the mining operation often outliving the tenure of those who originally planned them and, in some extreme cases, the companies who owned the mines from the very beginning. The overarching concern remains “planning for closure versus closure without planning”. But why is this case, what are the issues lurking, and could these problems guide towards new opportunities? In the recently published Foundational Project 2.2, ’Exploring the Issues in Mine Closure Planning’, the fundamental challenges and issues at the heart of MCP were identified. Following a thorough literature review, supplemented by surveys and interviews with select industry stakeholders, a comprehensive real-world model of the preferred MCP approach was formulated. Principles from complex adaptive systems theory were employed to account for the highly dynamic and interconnected MCP landscape as well as the limited value of reductionism.

Three key findings are presented in the CRC TiME Report: (1) an industry operator knowledge gap was identified, largely caused by the MCP responsibility being traditionally outsourced to external consultants; (2) current MCP approaches do not consider specifics and/or variables such as expected mine lifecycle, extraction method, commodity (and potential diversification of commodities), and feasibility levels; and (3) MCP lessons learned and/or success stories across the mining industry are not being shared. A chief outcome of Project 2.2 is the development of an Integrated Mine Transition Framework (IMTF), newly created to tightly knit all aspects of strategic mine planning and mining operations carried out over the lifetime of a mine. The IMTF will form the core of an integrated knowledge-based toolkit that affords the mining operator an advanced command and control capability during a MCP effort. Report 2.2 concluded that unless mining operators start taking true ownership of their MCP interests, the traditional crude approach we have witnessed for the last two centuries will persist.

There is, however, much to be hopeful for. In recent years, for example, the balance is returning to valuing social licence both here and around the world. Mine operators are increasingly recognising that social licence is equally as important as shareholder performance for ensuring the industry continues sustainably into the future. CRC TiME Report 2.2 showed how robust record-keeping of each MCP update iteration throughout the lifecycle of the mine, as well as tracking changes in regulatory requirements, is a major albeit not insurmountable challenge. If achieved, both regulatory authorities and mine operators can prepare mine closure plans that meet the mining regulator's clearance requirements without relying heavily on external experts and consultants. The current situation, however, is that neither regulators nor mine operators have an integrated solution to manage and effectively regulate crucial input.

Much more could be done right from the start of a mine’s lifecycle to envision an economically viable solution and garner commitment from a broader spectrum of stakeholder and interest groups. Germany, widely considered a world leader in MCP, can teach Australia a thing or two – such as their lignite operations in the North Rhenish regions of the country. An outstanding example of a post-mining land use that can inspire future MCP best practice is the well-known Eden Project located in Cornwall, United Kingdom, which saw a dramatic transformation of an abandoned Cornish China Clay Pit. The £141 million project, which was completed incrementally over two decades, culminated in the delivery of a world class eco-visitor attraction and was opened to the public on 17th March 2001.

More informed dialogue is needed to shift attitudes towards improved MCP and encourage early participation and investment, particularly from those who stand to benefit from the eventual outcome. In the case of The Eden Project, this included environmentalists, botanists, and the tourism sector. Mining professionals, executives, community stakeholders and shareholders should pause for a moment and think what could be possible when a periodically updated and sufficiently rich mine closure plan is produced from the start.

Australia has an opportunity to redefine what its own MCP success means.

Industry leaders are now calling for a new shared understanding of this success, recognising that the mining industry needs to connect with the sectors now driving post-mine development such as conservation, tourism, agriculture and energy. First Nations people’s land stewardship plays a critical role in developing this shared understanding. Australia is leading the world in building a culture of collaboration amongst diverse stakeholders with the unique cross sector partnership of CRC TiME working on MCP and driving innovation for positive mine closure.

Australia and its regional neighbours have several MCP exemplars for the domestic mining industry to learn from. For instance, the sensible transition approach taken by ASX-listed metals exploration company Kingston Resources as it enters Papua New Guinea to redevelop the Misima Island gold project, which fell victim to the soft gold price era of the 1990s. Other success stories include Australian coal mining company Coal & Allied’s alluvial land rehabilitation in the Hunter Valley of New South Wales and the rehabilitation of American aluminium producer Alcoa’s mine of approximately 600 hectares each year at its Huntly and Willowdale bauxite mining operations in the Darling Range in Western Australia.

Effective mine closure entails not only visualising and planning for the end of a mine’s life but, critically, also resolving the complexities around the ownership (or mandate) of the closure or transition from the very beginning.

Operating (left) and abandoned (right) mines in Australia. (Source: Vivoda et al., 2019)