Warwick Lorenz is Managing Director of Australian Pump Industries and a veteran of the water industry. He occasionally writes for various magazines.

Drought-Proofing a Sunburnt Country

Australian Poet and Fiction Writer Dorothea McKellar’s vision for Australia is still waiting to be realised. But where will all the water come from?

The mighty Ord River Dam, in The Kimberley north-east, where huge volumes of water are poured into the sea every day.

As we make our way through this third decade of the third millennium, Australians are confronted with the challenge of sustaining our world-class lifestyle in the face of unprecedented threats to our national security. Various geopolitical, public health, and socio-economic forces are now converging while most of the international scientific community describes climate change as out of our control.

Our resilient farmers survived a horrific record 6-year drought to be rewarded, serendipitously, with a glut of rain in 2020 and 2021. Consequently, our stewards of the land are currently enjoying unprecedented economic prosperity. To depend on the right climate at the right time, however, is a fragile strategy fraught with risk, as any Australian farmer will tell you. The only sustainability that counts in this country is water security.

Time to drought-proof Regional Australia

Despite personally advocating for it for a long time, the plan to drought-proof the inland of Australia is not new, in fact. John Bradfield CGM (1887-1943), the eminent Australian civil engineer who built the Sydney Harbour Bridge nearly a century ago, came up with a plan in the 1930s to turn rivers in Queensland and New South Wales backwards to feed the thirsty inland.

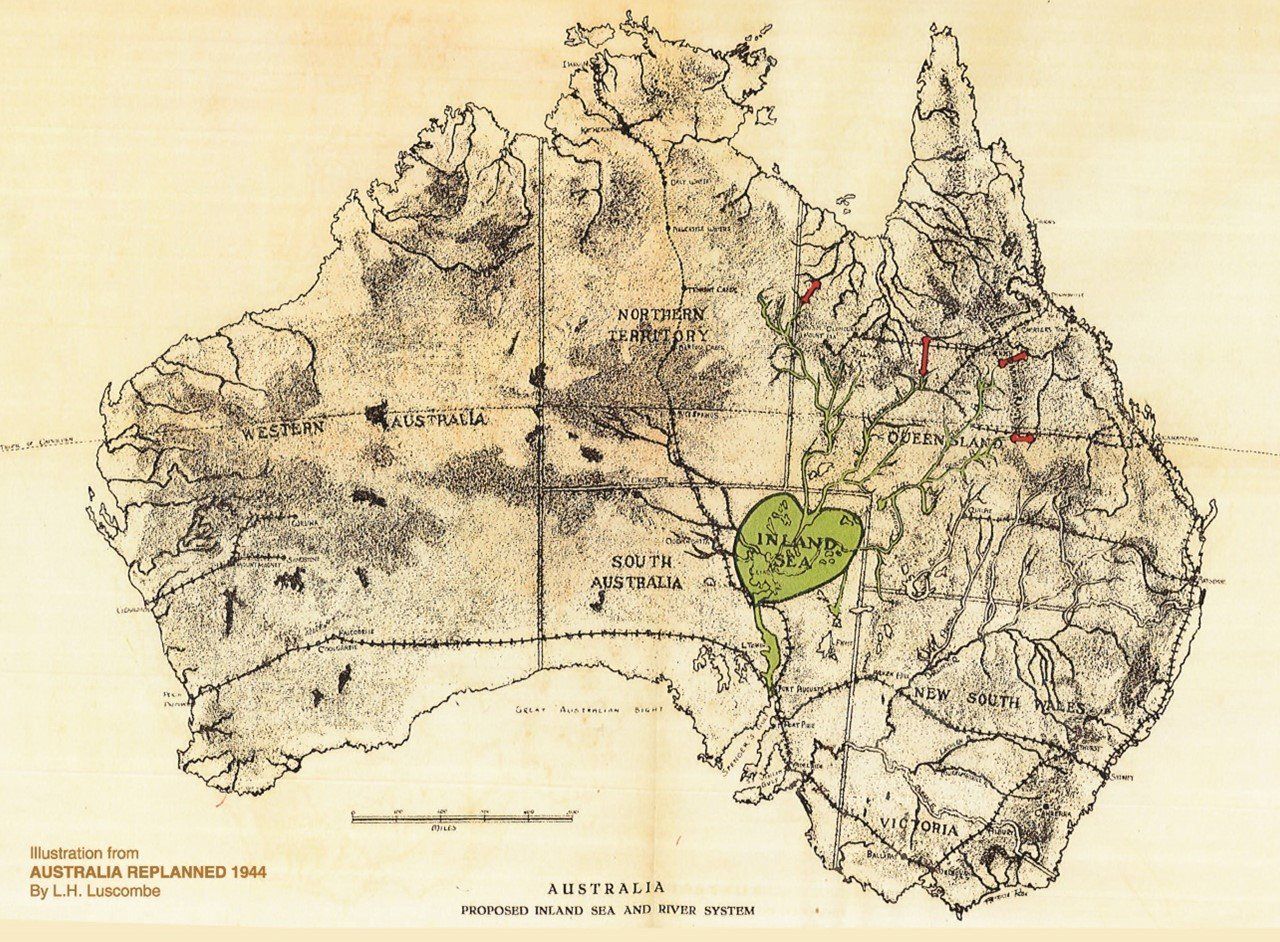

A few years later, towards the end of the World War II, and prior to becoming a journalist for the Truth and Daily Mirror publications in the 1950s, Leslie Henry Luscombe started promoting the same idea. His 177-page book, “Australia Replanned”, was published in 1945, though it was written in 1944 before the war had ended. His map, drawn by hydrologists at the time, showed how rainfall could be captured and stored for the “six lean years” to come.

Luscombe put forward the proposition of what a country of a mere seven or so million people able to put that huge an effort into the war should be capable of doing with the opportunities afforded by this vast island continent. He suggested our number one priority is water supply to the inland – such as dams and channels, similar to the Snowy River Scheme that was eventually constructed between 1949 and 1974.

: L.H. Luscombe’s map showing his dream, 82 years ago, of a vast inland sea. Wouldn’t it be great to build up our water storage and to refill the Great Australian Artesian Basin every year, instead of once every 6 years?

In my humble opinion, credit should go to Barnaby Joyce and Tony Abbott, who as then Deputy Prime Minister and Prime Minister of the country, later had a similar vision called the “Hundred Dams Project” in 2013. They realised that with much of our wealth being generated by farmers, regional Australia’s water security was a great opportunity to enlarge and grow the sector. The idea was to turn Bradfield and Luscombe’s dreams into reality albeit three-quarters of a century later. They argued that improved water supply to the agricultural sector could mean , Australia producing not just four times more food and fibre that we can consume ourselves but perhaps even 20 times that amount.

The idea of simply channelling water from Northern Australia, where it is abundant, to southern areas of the country that need it seems logical enough and technically feasible – at least in theory. This possible solution is, however, affected by a number of converging forces and therefore causing enormous complexity – social, technological, environmental, economic, and political. Hence, easier said than done.

Has anyone ever considered measuring the actual potential of a water transfer strategy, beginning with the question of “how much surplus water is there in cubic feet in Australia’s North?” and “what logistics are involved in bringing it south, where to, and to what benefit? “Interior rejuvenation” through the mass hydration of regional Australia, an “anti-desertification move”, ought be on the national agenda. Other parts of the world, including the Middle-East and Africa, are now engaging in this practice, especially if there are good water reserves in one part of said country.

The proposed Hells Gate Dam on the Burdekin River in northern Queensland, a transformational project for the region, could be a great start. Investing in the channels to get the water spread in a wide enough area to turn more land into quality high value cropping, however, should not be overlooked. Certainly, a project of this nature, which has attracted an historic AUD5.4 billion funding package from the Federal Government, has great potential to improve the “drought proofing” of regional Australia as largely serviced by the Murray Darling river system.

Nationally recognised water specialists like Simon Cowland-Cooper, a recent Order of Australia award recipient for his services to the irrigation industry, have ideas that are worth considering. Simon advocates that the Mount Foxton Dam proposal is another possible way of offering greater water security to both the eastern and western regions of the Great Dividing Range without the use of tunnels, pipelines or pumping units. This is achieved by substituting the proposed Hells Gate Dam with a far more appropriate structure 30 kilometres downstream to the Gorge situated Mt Foxton. At this location, a dam will be far higher than the Hells Gate Dam having an RL[1] 380 which will be able to provide two discharge gravity outlets to service both the East (RL 300) and West (RL 350) riverbed sides of the Range.

For the world’s driest inhabited continent, Australia’s next 5 to 10 year crippling drought is surely not a matter of if but when. While there are drip-feed improvements in attitudes happening and plenty of people with good opinions worth listening to on this nationally important commodity, what’s really needed is a tsunami of orchestrated action before it’s too late.

[1]

Relative Level Above Sea Level.